!THE BIBLIOGRAPHIC SECTION IS THE VERY REASON FOR WRITING THIS BLOG…ADDING BIBLIOGRAPHIC NOTES. Page numbers appear as such “12:”

to access the other pages, click on the alphabetical link

Because of my devotion to Benjamin Barber and because this is the initial of Bibliography, this is actually the entry page into my whole bibliography. Initially focused on my research topics (plurilingualism, multiculturalism, sociolinguistics), it now extends to Art, Politics (especially in the middle East) and any paper or book I wish to share with my readership. So this page actually has three parts (all the other alphabetical parts only have 2): PART ONE IS MY FULL BIBLIOGRAPHY, PART TWO is my bibliography for authors under letter B and PART THREE is a detailed account of PART TWO if I have added any notes.

Links to my bibliography from A to Z:

A B (this page) C D E F G H I J K L

Thus sharing my finding with my colleagues and inviting you to do likewise!

PART ONE: Here’s a total list of my almost 1532 titles;-)

(AACLME), Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (1991), ‘Language is good business’, (Melbourne: National Languages and Literacy Institute).

(AALC), Australian Language and Literacy Council (1994), ‘Speaking of business. The needs of business and industry for language skills’, (Canberra: National Board of Employment, Education and Training).

(de) Fontenay, Elisabeth (2011), Actes de Naissance (Sciences Humaines; Paris: Seuil).

(de)Toledo, Camille , 2009. Le Hêtre et le Bouleau. Essai sur la tristesse européenne (« Librairie du XXIe siècle »; Paris: Seuil ).

(ICMRP), Isan Culture Maintenance and Revitalization Program ‘Website’, [website], <http://icmrpthailand.org/en>, accessed Nov. 29th 2012.

Abanto, Alicia (2011), ‘Informe defensorial No. 152 Aportes para una policia nacional EIB a favor de los pueblos indigenas del Peru.’ paper given at World Conference on the Education of the Indigenous People (WIPCE 2011), Cusco, Peru.

Abbi, Anvita (ed.), (1996), Languages of tribal and indigenous peoples of India: the ethnic space (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas).

Abelin, Peter (2012), ‘Daniel Cohn-Bendit in Basel: “Israeli und Palästinenser müssen ihre Traüme begrenzen!’ Tachles, 14 Sept., sec. Schweiz.

Abella, Irving and Troper, Harold (1991), None is Too Many (Toronto: Lester).

Abid-Houcine, Samira (2006), ‘Plurilinguisme en Algérie’, (Sidi Bel Abbès).

— (2007), ‘Enseignement et éducation en langues étrangères en Algérie: la compétition entre le français et l’anglais’, in Daphné Romy-Masliah and Larissa Aronin (eds.), L’anglais et les cultures: carrefour ou frontière? (54; Paris: Revue Droit et Cultures, L’Harmattan).

Abou, Sélim (1981), L’identité Culturelle: Relations interethniques et problèmes d’acculturation, ed. Pierre Vallaud (Collection Pluriel; Paris: Anthropos) 249.

Abu-Laban, Yasmeen and Stasiulus, Daiva (1992), ‘Ethnic pluralism under siege: popular and partisan opposition to multiculturalism’, Canadian Public Policy, 4 (18), 365-86.

Achard, P. (1993), La Sociologie du Langage (Que-Sais-Je?; Paris: PUF).

Ackerman, Bruce (1980), Social justice in the liberal state (New Haven: Yale University Press).

Adachi, Ken (1976), The Enemy that Never Was (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart).

Adams, Phillip (1994), ‘A cultural revolution’, in Scott Murray (ed.), Australian Cinema (St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin), 61-70.

Adelaar, S (1995), ‘Borneo as a crossroads for comparative Austronesian linguistics’, in P Bellwood, JJ Fox, and D Tryon (eds.), The Austronesians: historical and comparative perspectives, 75-94 (Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies (ANU), Department of Anthropology).

Adelman, H., et al. (eds.) (1994), Immigration and Refugee Policy: Australia and Canada Compared (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press).

Adnan, A. H. M. (2010), ‘Losing language, losing identity, losing out – the case of Malaysian Orang Asli (native) children’.

Adnan, A. H. M. (2010), ‘“***k! It’s just the way we talk-lah!” Language, culture and identity in a Malaysian underground music community’.

Adnan, A. H. M. (2012), ‘Perdre sa langue, perde son identité, se perdre. Le cas des enfants Orang Asli (aborigènes) de Malaisie.’ Droit et Cultures, 63 (S’entendre sur la langue), 79-100.

Adorno, T. W. and ., Horkheimer. Max (2002), Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. Edmund Jephcott. (Stanford: Stanford UP).

AFP-Jiji (1999), ‘Crocodile Dundee’s Death Puzzles the Police’, The Japan Times, Aug.6, p. 5.

Agarwal, S. (1995), Minorities in India: a study in communal process and minority rights (Jaipur: Arihant Publishing House).

Akcan, Sumru (2004), ‘Teaching Methodology in a French-Immersion Class’, Bilingual Research Journal, 28 (2), 267-77.

Alatis, J.E. and Staczek, J.J. (eds.) (1970), Perpectives on Bilingualism and Bilingual Education (Georgetown: Georgetown University Press).

Al-Azmeh, Aziz, et al. (2004), L’identité, ed. Nadia Tazi (French edn., Les Mots du Monde; Paris: Editions La Decouverte).

Al-Azmeh, Aziz (2004), ‘Une Question Post-Moderne’, L’identité (French edn., Les Mots du Monde; Paris: Editions La Decouverte), 11-24.

Ali, M.O. (2003), ‘Enseignement du Tamazight à Sidi Bel Abbès’, Le quotidien d’Oran, samedi 10 mai 2003, p. 13.

Alimi, Eitan Y. and Meyer, David S. (2012), ‘Seasons of Change: Arab Spring and Political

Opportunities’, Swiss Political Science Review : , 17 (4), 475-79.

Allievi, Stefano ( 2003), ‘Multiculturalism in Europe’, Muslims in Europe Post 9/11: Understanding and Responding to the Islamic World (St Antony’s College, Oxford).

Al-Mulhim, Abdulateef , 2012, Saturday 6 October, and am, Last Update 6 October 2012 2:53 (2012), ‘Forget Israel. Arabs are their own worst enemy’, Arab News, sec. op’ed.

Alvarez, Lizette (1997), ‘It’s the Talk of Nueva York: The Hybrid called Spanglish”‘, New York Times, 25 March.

Amador-Moreno, Carolina P and McCafferty, Kevin (2012), ‘Linguistic identity and the study of Emigrant Letters: Irish English in the making ‘, Lengua y migración / Language and Migration, 4 (2).

Amar, Akhil Reed (1998), The Bill of Rights (New Haven and London: Yale University Press) 412.

— (2000), ‘Allow the Electoral College to Do Its Usual Job, and Then Abolish It’, New York Times and International Herald Tribune, November 10, 2000, p. 8.

radio interview (1999) (France Inter).

Amon, Ulrich and Hellinger, Marlis (eds.) (1992), Status Change of Languages 1 vols. (Change of Language Structure and Language Status, 1; Berlin/London: Walter de Gruyter) 547 pp.

Amselle, Jean-Loup (2001), Vers un multiculturalisme français (Paris: Flammarion).

Anaya, S. James (1995), ‘The Capacity of International Law to Advance Ethnic or Nationality Rights Claims’, in Will Kymlicka (ed.), The Rights of Minority Cultures (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 387.

Anderson, B (1983), Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso).

Anderson, Elijah (1999), ‘The social situation of the black and white identities in the corporate world.’ in Michèle Lamont (ed.), The Cultural Territories of Race: Black and White Boundaries (University of Chicago Press), 3-29.

Anderson, Digby (2000), ‘When words change meaning -and do violence to the truth: Social affairs Unit has celebrated its 20th anniversary with a dictionary that analyses the linguistic abuses of political correctness’, The Daily Telegraph, Nov.23d, p. 28.

Andreas, Huyssen (1988), After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture and Postmodernism (London: Macmillan).

Andreoni, G (1967), ‘Australitalian’, University Studies in Australian, (5), 114-19.

Appel, René and Muysken, Pieter (1987), Language Contact and Bilingualism (London: Edward Arnold).

Archer, Margaret (2005), ‘Comments’, in Neil J. Smelser, University of California, Berkeley (ed.), 37th International Institute of Sociology Conference: Sociology and Cultural Sciences (Folket Hus, Kongresshallen A: University of Warwick, UK).

Arendt, Hannah (1979 , 1951), The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Harcourt Brace.).

— (1993), Auschwitz et Jérusalem (Paris: Deuxtemps Tierce (Presses Pocket Agora)).

Arieli, Shaul (2011), People and Borders (Tel-Aviv: Kapaim) 477.

Arieli, Shaul (2012), ‘Abu Mazen wants a state, not the right of return: Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas sees the UN bid as his last, best chance to negotiate with Israel.’ Haaretz, 18.11.12.

Arieli, Shaul ‘Website’, [website], <http://www.shaularieli.com>.

Armitage, A. (1995), Comparing the Policy of Aboriginal Assimilation: Australia, Canada and New Zealand (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press).

Aronin, Larissa and Barkon, Elisheva (2007), ‘L’anglais et les cultures: carrefour ou frontière?’ Droit et Cultures (54; Paris: L’Harmattan).

Asante, Mlefi Kete (1990), Kemet, Afrocentricity, and Knowledge (Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press).

ASCD (1987), ‘Building an Indivisible Nation: Bilingual Education in Context’, (Alexandria, Virginia: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development).

Ashworth, M. (1988), Blessed with Bilingual Brains: Education of Immigrant Children with English as a Second Language (Vancouver: Pacific Educational Press).

AssociatedPress, ‘L’anglais est la langue de l’avenir pour les Suisses, selon deux sondages’, AP Wire, dimanche 24 septembre 2000, 15h16.

Atkinson, Michael M. (ed.), (1993), Governing Canada: Institutions and Public Policy (Toronto: Harcourt Brace).

Attabi, Said (2012), ‘Algérie : paysage sociolinguistique et alternance codique’, El Watan.com, p. 1.

Auer, Peter (2012), ‘Standardization and diversification: the urban sociolinguistics of German’, paper given at Languages in the City, Berlin, 21-24 August, 2012.

Aufheide, Patricia (ed.), (1992), Beyond PC: Toward a Politics of Understanding (Cincinati: Graywolf Press).

August-Zarebska, Agnieszka (2010), ‘Judeo-Spanish proverbs as an example of the hybridity of Judezmo

language and Sephardic culture ‘, Languages in Contact 2010: A Book of Abstracts (Wroclaw: Philological School in Higher Education, Wrolaw (Poland)).

Australia (1982), ‘Towards a National Policy’, (Canberra: Department of Education).

— (1992), ‘A Matter of Survival: Language and Culture’, (Canberra: House of Representatives Enquiry into the Maintenance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages).

— (1994), ‘Asian Languages and Australia’s Economic Future’, (Council of Australian Governments).

Bader, Veit. (1995), ‘ Citizenship and exclusion: radical democracy, community and justice’, Political Theory, 2 (23), 211-46.

Baggioni, D., et al. (1992), Multilinguisme et développement dans l’espace francophone (Institut d’Etudes Créoles et Francophones et Didier Erudition).

Bailey, Guy, Maynor, Nathalie, and Cukor-Avila, Patricia (eds.) (1991), The emergence of Black English : Text and Commentary (African-American English: Structure, History and Use, Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins).

Bailey, Guy and Thomas, Erik (1998), ‘Some aspects of African American Vernacular English Phonology’, in Slikoko S. Mufwene, et al. (eds.), African-American English: Structure, History and Use (London: Routledge), 85.

Bailyn, Bernard (1967), The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, Massachusets: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press) 335.

Baker, Colin (1993), Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd).

Baker, Geoff (1994), ‘Stepdad gets 2 years in sex assault’, The Gazette, 15 janvier.

Bakhtin, Michael (1981), ‘The dialogic imagination: Four Essays’, in M. Holquist and C. Emerson (eds.), (Austin: University of Texas Press).

Balibar, R., , Paris (1993), Le Colinguisme (Que-Sais-Je?: PUF).

Balibar, R. (2008), ‘A propos du sionisme : messianisme et nationalisme’, l’Agenda de la pensée contemporaine, (9).

Balio, Tino (1990), Hollywood in the Age of Television (Boston: Unwin Hyman).

Balla, Monkia, Bujanovic, Sandra, and Illic, Maria (2012), ‘Hungarian in contemporary Belgrade: a case of compartmentalized language’, paper given at Languages in the City, Berlin, 21-24 August, 2012.

Ballantyne, Davidson et McIntyre ‘Ballantyne, Davidson et McIntyre c. Canada’, (31 décembre 1993 edn.).

Ballin, Luisa and Wermus, Daniel (2012), ‘«Je rêve d’un Mandela israélien»’, Le Temps, Lundi26 novembre sec. Proche-Orient

Baraby (2012), in Fernand De Varennes (ed.), Droits Linguistiques, inclusion et la prévention des conflits ethniques (Chiang Mai).

Barber, Benjamin R. (1993), L’Excellence et l’Egalité: de l’Education en Amérique, eds Jean Heffer and François Weil, trans. Vincent Michelot and Weil François (Cultures Américaines; Paris: Belin) 315.

Barber, Benjamin (1995), ‘Face à la Retribalisation du Monde’, Esprit, (Juin 1995), 132-44.

Barber, Benjamin R. (1996), Djihad vs McWorld, trans. Valois Michel (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer) 303.

Barber, Benjamin (2007), Consumed: How Markets Corrupt Children, Infantilize Adults and Swallow Citizens Whole (W.W. Norton and Company) 406.

— (2009), ‘Interdependence Day’, Art, Religion, and the City in the Developing World of Interdependence (Istanbul).

Barber, Benjamin R. (2010), ‘America’s Knowledge Deficit’, November 10, 2010.

Barber, Benjamin (2010), ‘America’s knowledge deficit’, The Nation, Nov. 29, 2010.

— (2010), ‘Interdependence Day’, SUSTAIN/Ability (in climate, culture and civil society) (Berlin).

Barber, Benjamin, et al. (2012), ‘Welcome address, opening remarks’, paper given at 10th Interdependence Day: Culture, Justice and the Arts in the Age of Interdependence, Los Angeles, September 8th, 2012.

Barber, Benjamin (2012), ‘Interdependence Day’, 10th Interdependence Day: Culture, Justice and the Arts in the Age of Interdependence (Los Angeles).

Barghouti, Mustafa , et al. (2012), ‘One State, Two-State, Green State, Blue State’, J Street Conference Making History (Washington D.C.).

Barnavi, Elie (2011), ‘Se taire s’apparente à non-assistance à pays en danger’, in David Chemla (ed.), JCall: les raisons d’un appel (Paris: Liana Levi ), 19-24.

Barnett, David and Goward, Pru (1997), John Howard, Prime Minister.

Baron, Dennis (1991), The English-Only Question: An Official Language for Americans? (Yale University Press).

Barry, Brian. (1991), ‘Self-government revisited’, Democracy and power: essays in political theory, Oxford:.

Barth, Frederik. (1969), Ethnic groups and boundaries. (Boston: Little Brown).

Baskin, Cyndy and Summer, Krystal (2011), ‘From Assimilation to transformation: Incorporating indigenous education in the main instutions of post-secondary studies’, paper given at World Conference on the Education of the Indigenous People.

Baskin, Gershon (2012), ‘Negotiating for Gilad Shalit’s Freedom: A discussion with Gershon Baskin’, J Street: Making History (Washington D.C.).

Bastarache, Michel (2012), ‘Les garanties linguistiques: droits humains ou instruments d’intégration sociale au Canada’, in Fernand De Varennes (ed.), Droits Linguistiques, inclusion et la prévention des conflits ethniques (Chiang Mai).

Batterbee, K. (2010), ‘Expectations mismatch in multiple-language polities’, paper given at “Language, Law and the Multilingual State” 12th International Conference of the International Academy of Linguistic Law Bloemfontein, 1-3 november 2010.

Baubock, Rainer (1994), Transnational Citizenship: Membership and Rights in Transnational Migration (Aldershot: Edward Elgar).

Bauer, Alain (2003), ‘Laicité, mode d’emploi: les pouvoirs publics face à l’offensive des communautarismes’, Le Figaro, 17 novembre 2003, p. 15.

Baugh, John (1983), Black Street Speech: its history, structure and Survival (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press).

— (1988), ‘Language and Race: Some Implications for Linguistic Science’, in F. Newmeyer (ed.), Linguistics: The Cambridge Survey (4; Cambridge: Cambridge University), 64-74.

Baugh, A. and Cable, T. (1993), A History of the English Language (4th edn.; Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall).

Baugh, John (1993), Black Street Speech (Austin, Texas: University of, Texas Press).

— (1997), ‘What’s in a name? That by Which We Call the Linguistic Consequences of the African Slave Trade’, The quarterly of the National Writing Project, (19), 9.

— (1998), ‘Linguistic, Education, and the Law: Educational Reform for African-American Language Minority Students’, in Slikoko S. Mufwene, et al. (eds.), African-American English: Structure, History and Use (London: Routledge), 282-301.

— (1999), Out of the Mouths of Slaves: African American Language and Educational Malpractice (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press) 190.

Bearak, Barry (1997), ‘Between Black and White’, New York Times, July 27, p. sec.1, p.1.

Beaugé, Marc (2010), ‘L’English Defence League, en guerre contre l’islam’, LesInrocks.com

Beck, Ulrich (2004), ‘Cosmopolitical Realism: On the Distinction between Cosmopolitanism in Philosophy and the Social Sciences’, Global Networks, 4 (2), 109-225

— (2006), Cosmopolitan Vision (Cambridge: Polity Press).

— (2006.), Qu’est-ce que le cosmopolitisme ? (Paris: Aubier).

Becker, Gary (1957), The Economics of Discrimination (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

— (1976), The Economic Approach to Human Behavior (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Bédarida, Catherine (2000), ‘Ahmadou Kourouma, le guerrier-griot’, Le Monde, Mercredi 1er Novembre 2000, p. 15.

Bedos, Nicolas (2012), Une Année Particulière, journal d’un mythomane, (vol.2; Paris: Robert Laffont).

Beeson, Mark (1997), ‘ Australia, APEC, and the Politics of Regional Economic Integration’, Asia Pacific Business Review, ( 2.1).

Behr, Edward (1995), Une Amérique qui fait peur: la liberté est-elle devenue l’instrument d’une nouvelle tyrannie? (Paris: Edward Behr et les Editions Plon) 325.

Beinart, Peter (2012), ‘To save Israel, boycott the settlements (OpEd)’, New York Times

Beinart, Peter (2012), ‘The Crisis of Zionism: Premiere Book Event with Author Peter Beinart’, J Street: Making History (Washington D.C.).

Bell, David V.J. (1992), The roots of disunity : a study of Canadian political culture (Toronto: Oxford University Press) 200.

Bell, Pat (1999), ‘Jokes on Ebonics’.

Bellonie, Jean-David

Guérin, Emmanuelle (2011), ‘La place du français en question dans les représentations de locuteurs francophones en contact avec d’autres langues’, paper given at Langues en contact: le français à travers le monde, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 16-18 septembre 2011.

Ben-Ami, Jeremy (2012), ‘Welcome remarks’, J Street: Making History (Washington D.C.).

Bencomo, Clarisa and Colla, Elliott (1993), ‘Area Studies, Multiculturalism, and the Problems of Expert Knowledge’, Bad Subjects Web Page, (5).

Benes, Marie-France (1999), ‘L’éducation interculturelle au service du savoir-vivre ensemble: le cas de l’école québécoise’, Revue Québécoise de Droit International: actes du Séminaire international de Montréal sur l’éducation interculturelle et multiculturelle., 12 (1), 25-32.

Benhabib, S. (2004), The Rights of Others (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Bennett, David (ed.), (1993), Cultural Studies: Pluralism & Theory (Melbourne University Literary and Cultural Studies, 2; Melbourne: Department of English, University of Melbourne).

— (ed.), (1998), Multicultural states: rethinking difference and identity (New York: Routledge).

Benrabah, Mohamed (2004), ‘Language and Politics in Algeria’, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 10 (78), 59-78.

Bensekat, Malika (2011), ‘Le français conversationnel des jeunes de Mostaganem: “une forme hybride”‘, paper given at Langues en contact: le français à travers le monde, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 16-18 septembre 2011.

Bensoussan, Georges (2011), ‘Eviter l’Etat unique et arabe’, in David Chemla (ed.), JCall: les raisons d’un appel (Paris: Liana Levi ), 25-36:.

— (2012), Juifs en pays arabes : lLe grand déracinement 1850- 1975 (Paris: Tallandier).

Benzenine, Belkacem (2012), ‘La langue algérienne mérite d’être valorisée’, El-Watan, 16 mars 2012, sec. Culture.

Bereiter, Carl and Engelmann, Siegfried (1966), Teaching disadvantaged children in the pre-school (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall).

Berman, Paul (ed.), (1992), Debating PC: The Controversy over Political Correctness on College Campuses (New York: Laurel).

Berman, Antoine (2008), L’Âge de la traduction. « La tâche du traducteur » de Walter Benjamin, un commentaire (

: PU Vincennes).

Bernard, Philippe (2004), ‘Interview de Didier Lapeyronnie, prof de sociologie à l’université Victor Segalen de Bordeaux’, Le Monde, mardi 6 juillet 2004, p. 6.

Bernstein, Richard (1994), ‘Guilty If Charged’, New York Times Review of Books, p. 1994.

— (1995), Dictatorship of virtue: How the battle over Multiculturalism is reshaping our Schools, our Country and our Lives (Vintage Books; New York: Random House) 379.

Berri, Y (1973), ‘Algérie: la révolution en arabe’, Jeune Afrique, (639), 14-18.

Bettoni, Camilla and Gibbons, John (1988), ‘Linguistic pluralism and language shift: a guise-voice study of the Italian community in Sydney’, International Journal of the Sociology of Language, (72).

Betts, Katharine (1991), ‘Australia’s Distorted Immigration Policy’, in D. Goodman, D.J. O’Hearn, and C. Wallace-Crabbe (eds.), Multicultural Australia: the challenges of change (Melbourne: Scribe), 149-77.

Bezzina, Anne-Marie (2011), ‘Le contexte maltais: des contacts omni-présents’, paper given at Langues en contact: le français à travers le monde, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 16-18 septembre 2011.

Bhargava, R, Bagchi, Amiya K., and R., Sudarshan (eds.) (1999), Multiculturalism, liberalism and democracy (Delhi: Oxford University Press).

Bharucha, Rustom ‘ Politics of culturalism in an age of globalisation: discrimination, discontent and dialogue’, Economic and Political Weekly, 8 (34), 477-89.

Bibby, R.W. (1990), Mosaic Madness: The Poverty and Potential of Life in Canada (Toronto: Stodart).

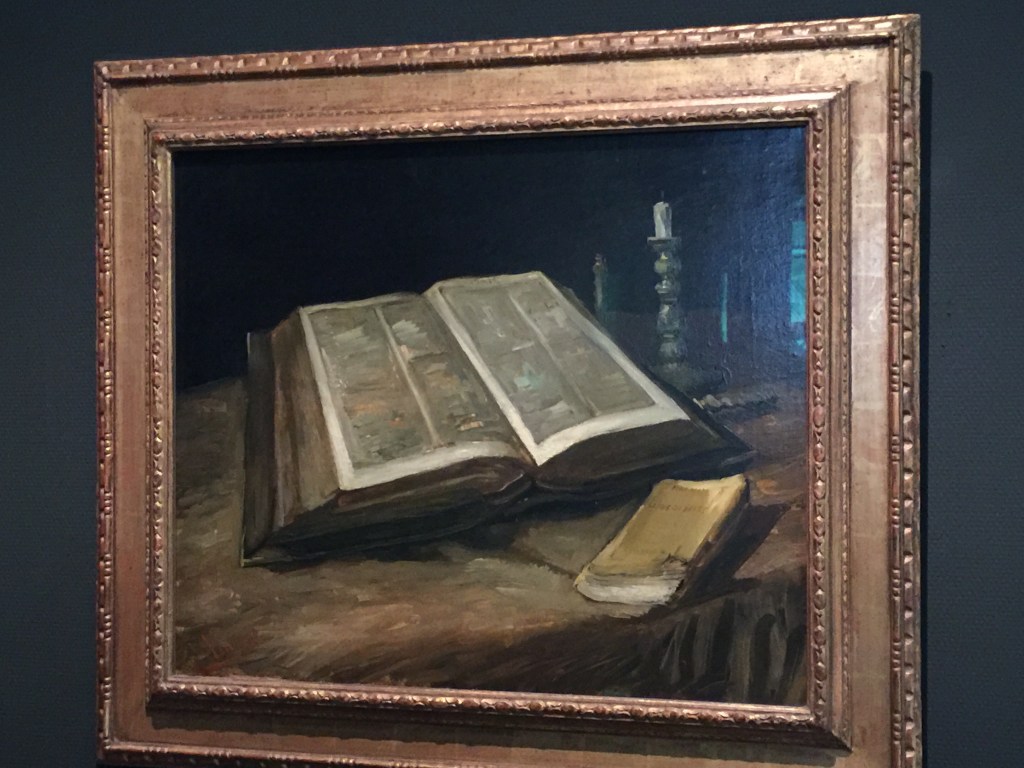

Bible ‘Chapter 8, art. 9’, The Book of Esther

Bikales, Gerda. (1986), ‘Comment: the other side’, International Journal of the Sociology of Language, (60), 77.

Binder, Amy (1999), ‘Friend and Foe: boundary work and collective identity in the afrocentric and multicultural curriculum movement in american public education’, in Michèle Lamont (ed.), The Cultural Territories of Race: Black and White Boundaries (University of Chicago Press), 221-48.

Bisaillon, Robert (1999), ‘Diversité et cultures: Pour une école québecoise inclusive et non discriminatoire’, Revue Québécoise de Droit International, 12 (1), 13-15.

Bissonnette, Lise (1990), ‘ Culture, politique et société au Québec’, (Centre canadien d’architecture: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation).

— (1995), ‘Préface à l’ouvrage de Bissoondath, Neil, Le Marché aux Illusions: la méprise du multiculturalisme’, (Montréal: Boréal).

Bissoondath, Neil (1994), Selling Illusions: The Cult of Multiculturalism in Canada (Toronto: Penguin Books Canada).

— (1995), Le Marché aux Illusions: la méprise du multiculturalisme, trans. Jean Papineau (Liber; Montréal: Boréal) 243.

Biton, Michael (2012), ‘keynote speech as the Mayor of Yerucham’, J Street: Making History (Washington D.C.).

Blake, William (1757-1827), ‘Jerusalem’.

Blake, N.F. (1996), A History of the English Language (New York: New York University Press) 382.

Block, Irwin (1994), ‘Women outraged by judge’s remarks’, The Gazette, 15 janvier.

Bloom, David and Grenier, Gilles (1992), ‘Earnings of the French Minority in Canada and the Spanish Minority in the US’, in B. Chiswick (ed.), Immigration, Language and Ethnicity (Washington D.C.: The AEI Press), 379-409.

Bloomfield, Leonard (1933), Language (New York: Holt).

OAKLAND’S AFRICAN AMERICAN TASK FORCE IS ON THE CUTTING EDGE OF EDUCATIONAL REFORM (1997).

Body-Gendrot, Sophie (1991), Les Etats-Unis et leurs immigrants, ed. Isabelle Crucifix (Les études de la documentation Française, 4941; Paris: la documentation Française) 149.

Bolkestein, Fritz and Rocard, Michel (2006), Peut-on réformer la France? (Paris: Autrement).

Bonbled, Nicolas (2012), in Fernand De Varennes (ed.), Droits Linguistiques, inclusion et la prévention des conflits ethniques (Chiang Mai).

Bottomley, G. and M., de Lepervanche (1984), Ethnicity, Class and Gender in Australia (London: George Allen & Unwin).

Bouchard Ryan, E. and H., Giles (1982), Attitudes towards Language Variation: Social and Applied Context (Edward Arnold).

Boudon, Raymond (1998), ‘Les dangers du communautarisme ou les effets pervers de la coopération’.

Bourdieu, Pierre and Passeron, Jean-Claude (1970), La reproduction: Eléments pour une théorie du système d’enseignement (Paris: Les Editions de Minuit).

Bourdieu, P. (1981), Le Français chassé des sciences (Paris: CIREEL).

Bourmaud, Philippe (2008), ‘Une histoire de la Palestine : enjeux et périls : Recension de Gudrun Krämer, A History of Palestine. From the Ottoman conquest to the

founding of the State of Israel, Princeton / Oxford, Princeton University Press, 2008.’ la Vie des Idées.

Bouton, Charles (1984), La Neurolinguistique (Que-Sais-Je?; Paris: PUF).

— (1993), La Linguistique appliquée (3ème edn., Que-Sais-Je?, 1755; Paris: PUF) 127.

Braen, André (2012), ‘La protection juridique des langues autochtones du Canada’, in Fernand De Varennes (ed.), Droits Linguistiques, inclusion et la prévention des conflits ethniques (Chiang Mai).

Braibant, Guy (1998), ‘Le cinquantenaire de la Déclaration universelle des droits de l’homme Personnalité juridique’, Le Monde Interactif.

Brash (1981), Black English and the Mass Media (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press).

Brass, Paul. (1974.), Language, religion and politics

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

— (1991), Ethnicity and nationalism: theory and comparison (Delhi: Sage).

Breton, Roland (1995), Géographie Des Langues (3ème edn., Coll. Que-Sais-je, #1648; Paris: PUF) 127.

Breton, Roland J.L. (1996), Atlas of the languages and ethnic communities of South Asia. (Delhi: Sage).

Brezigar, B. (2010), ‘From Maastricht to Lisbon – Development of language lesgislation in the EU Treaty’, paper given at “Language, Law and the Multilingual State” 12th International Conference of the International Academy of Linguistic Law Bloemfontein, 1-3 november 2010.

Brohy, Claudine (1997), ‘Bilinguisme naissant ou bilinguisme évanescent? Enseignement plurilingue et interculturel en Suisse.’ Interdialogos, 2, 7-11.

Brohy, Claudine and Bregy, Anne-Lore (1998), ‘Mehrsprachige und plurikulturelle Schulmodelle in der Schweiz oder: What’s in a name?’ Bulletin suisse de linguistique appliquée., 2, 85-99.

Brohy, C. (2010), ‘Concluding remarks’, paper given at “Language, Law and the Multilingual State” 12th International Conference of the International Academy of Linguistic Law Bloemfontein, 1-3 november 2010.

Brohy, C. & K. Herberts (2010), ‘Symposium “Language policies and language surveys in bilingual municipalities”: Bilingualism and the city: measuring the quality of linguistic cohabitation in two bilingual towns in switzerland AND Finnish bilingualism like Heinz Ketchup – at least 57 varieties!’ paper given at 12th International Conference of the International Academy of Linguistic Law”: Language, Law and the Multilingual State”. Bloemfontein: Free StateUniversity.

Brohy, Claudine (2012), ‘Plurilinguisme et citoyenneté: les instruments de la démocracie directe’, in Fernand De Varennes (ed.), Droits Linguistiques, inclusion et la prévention des conflits ethniques (Chiang Mai).

Brook, S. (1987), Maple Leaf Rag (Hamish Hamilton).

Brooke, James (2000), ‘Canada: Les Eglises ruinées par les Indiens?’ Courrier International (The New York Times), (523), 22.

Brooks, Roy L. (1996), Integration or Separation: A Strategy for Racial Equality (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press) 348.

Broome, R. (1994), Aboriginal Australians: Black Responses to White Dominance 1788-1994 (St Leonards NSW: Allen & Unwin).

Brown, Jennifer and Wilson, C. Roderick (1986), ‘The Northern Algonquians: a regional overview’, in B. Morrison and Wilson R. (eds.), Native Peoples: the Canadian Experience (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart), 143-49.

Brown, Dan (2001), Angels and Demons (paperback 2nd edn.; New York).

Brownlie, Ian (1988), ‘The Rights of Peoples In Modern International Law’, in James Crawford (ed.), The Rights of Peoples (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 1-16.

Bruckner, Pascal (1994), Le vertige de Babel, cosmopolitisme ou mondialisme (Paris: Arléa).

Brutt-Griffler, Janina (2003), ‘World English: A study of its development’, Journal Language Policy, 3 (October, 2003).

Bryson, Bethany (1999), ‘Multiculturalism as a moving moral boundary: literature professors redefine racism’, in Michèle Lamont (ed.), The Cultural Territories of Race: Black and White Boundaries (University of Chicago Press), 249-88.

Buchanan, Allen (1991), Secession: The Legitimacy of Political Divorce (Boulder: Westview Press).

Buckskin, Peter and O’Brien, Lewis (2011), ‘From Policy to Praxis, the time for talking is over’, paper given at World Conference on the Education of the Indigenous People (WIPCE 2011), Cusco, Peru.

Bullock , A. and Stallybrass, O. (eds.) (1977), The Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (London: Fontana Books).

Bunge, Robert (1992), ‘Language: the Psyche of a People’, in James Crawford (ed.), Language Loyalties: A source-book on the Official English Controversy (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press), 376-80.

Burch, Ernest S. (1986), ‘The Eskaleuts: a regional overview’, in B. Morrison and Wilson R. (eds.), Native Peoples: the Canadian Experience (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart), 67-77.

Bureau, of Immigration and Population Research (1994.), Australia’s Population Trends and Propects 1993 (Canberra,: Australian Government Publishing Service).

Burnaby, B. (1982), Language in Education among Canada’s Native Peoples (Toronto: OISE Press).

— (ed.), (1985), Promoting Native Writing Systems in Canada (Toronto: OISE Press).

Burnaby, B. and Cumming, A. (eds.) (1992), Socio-political Aspects of ESL in Canada (Toronto: OISE Press).

Burnet, Jean. (1975), ‘Multiculturalism, immigration, and racism’, Canadian Ethnic Studies, 1 (7), 35-39.

Burridge, Kate, Foster, Lois, and Turcotte, Gerry (1997), Canada-Australia: Towards a Second Century of Partnership (International Council of Canadian Studies: Carleton University Press).

Bustamante, Jorge (1989), ‘Fronteras Mexico-Estados Unidos: reflexiones para un marco teorico’, Frontera Norte, 7-24.

Butler, J. (ed.), (1987.), Democratic liberalism in South Africa: its history and prospect. (Middletown Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press).

Butlin, N.G., A., Barnard, and Pincus, J.J. (1982), Government and Capitalism (Sydney: Allen and Unwin).

Bybee, Keith J. (1998), Mistaken Identity: The Supreme Court and the Politics of Minority Representation (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press) 1994.

Byrdsong, Michael D. (1994), ‘The question of the “N” word: the when, the why the who, and the what”.’ (The City College: The City University of New York term paper for course on African-American English).

Cain, Bruce. (1992.), ‘Voting rights and democratic theory: toward a colour-blind society’, in Grofman B. and Davidson C. (eds.), Controversies in minority voting: the voting rights act in perspective (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution).

Cairns, Alan. (1991), ‘Constitutional change and the three equalities’, in Ronald Watts and Douglas Brown (eds.), Options for a new Canada. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Cairns, Alan. (1995), ‘Aboriginal Canadians, citizenship and constitution’, Reconfigurations: Canadian citizenship and constitutional change (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart).

Cajete, Gregory, Nuuhiwa, Kalei, and Laimana, Kalei (2011), ‘Ancestral knowledge of Sacred places’, paper given at World Conference on the Education of the Indigenous People (WIPCE 2011), Cusco, Peru.

Calhoun, Craig (2005), ‘ Cosmopolitanism and Belonging’, in Masamichi Sasaki (ed.), 37th International Institute of Sociology Conference: Migration and Citizenship (Stockholm, Norra Latin, Aula 3d Floor: NYU).

California ‘Regents of the State of California v. Bakke’.

Calvet, L.J. (1974), Linguistique et Colonialisme

Petit Traité de Glottophagie (Paris: Bibliothèque Scientifique Payot).

— (1981), Les Langues Véhiculaires (Paris: PUF Que-Sais-Je?).

Calvet, Louis-Jean. (1993), L’Europe et ses Langues (Paris: Plon).

Calvet, Louis-Jean (1996), Les Politiques Linguistiques (3075; Paris: PUF Que-Sais-Je?) 127.

Calvet, Louis-Jean. (2004), Essais de linguistique: la langue est-elle une invention des linguistes? (Paris: Plon) 250.

Canada (1990), Loi sur le multiculturalisme canadien, Guide à l’intention des Canadiens (Ottawa).

Canada, Patrimoine (1999), ’10ème Rapport annuel sur l’application de la Loi sur le multiculturalisme canadien 1997-1998′, (Ottawa: Ministère du Patrimoine canadien).

Canada, Statistique (2012), ‘Les langues immigrantes au Canada’.

Canovan, Margaret (1996), Nationhood and Political Theory (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar).

Caravedo, Rocío and Klee, Carol A. (2012), ‘Migración y contacto en Lima: el pretérito perfecto en las cláusulas narrativas’, Lengua y migración / Language and Migration, 4 (2).

Carby V., Hazel (1999), Cultures in Babylon (London and New York: Verso) 282.

Carens, Joseph ‘Citizenship and aboriginal self-government’, (Ottawa: Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples).

Carens, Joseph. (1987.), ‘Aliens and citizens: the case for open borders’, Review of Politics, 3 ( 49).

Caron, Thérèse (2012), ‘Diversité linguistique au Québec’, in Fernand De Varennes (ed.), Droits Linguistiques, inclusion et la prévention des conflits ethniques (Chiang Mai).

Carter, Philipp M. (2012), ‘Language and Identity Formation in “New” U.S. Latino Communities Phillip M. Carter

‘, in Florida International University (ed.), (Miami).

Carver, Craig (1992), ‘The Mayflower to the Model T: the development of American Eglish’, in T.W. Machan and Scott Ch.T. (eds.), English in its Social Contexts: Essays in Historical Sociolinguistics, (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 131-54.

Casey, John W. (1998), ‘The Ebonics Controversy: Critical Perspectives on African-American Vernacular English’, The Keiai Journal of International Studies, 1 (1), 179-214.

Cashmore, Ellis (1996), Dictionary of Race and Ethnic Relations (London: Routledge).

Casier, Marlies and Jongerden, Joost (eds.) (2010), Nationalisms and Politics in Turkey: Political Islam, Kemalism and the Kurdish Issue (Routledge Studies in Middle Eastern Politics: Routledge) 236.

Cassen, Bernard (2005), ‘on peut déjà se comprendre entre locuteurs de langues romanes: Des confins au centre de la galaxie’, Le Monde Diplomatique, (Janvier 2005), 22.

— (2005), ‘on peut déjà se comprendre entre locuteurs de langues romanes: Un monde polyglotte pour échapper à la dictature de l’anglais’, Le Monde Diplomatique, (Janvier 2005), 22.

Castellanos, Diego (1992), ‘A Polyglot Nation’, Language Loyalties: A source-book on the Official English ControversyCrawford, James (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press), 13-18.

Castile, George Pierre (1998), To Show Heart (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press) 227.

Castles, Stephen (1997), ‘Multicultural citizenship: a response to the dilemna of globalisation and national identity’, Journal of Intercultural Studies, 18 (1).

Castonguay, Charles (1994), L’assimilation linguistique: mesure et évolution 1971-1986, ed. Conseil de la Langue française (Sainte-Foy, Québec: Publicatiosn du Québec) xix +243 pp.

Castro, Max J. (1992), ‘On the Curious Question of Language in Miami’, in James Crawford (ed.), Language Loyalties: A Sourcebook on the Official English Controversy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 178-86.

Cernadas Carrera, Carlos (2012), ‘La migración sefardí en la Amazonia brasileña: lengua hakitía e identidad’, Lengua y migración / Language and Migration, 4 (2).

Cham, Mbye B. and Andrade-Watkins, Claire (1988), Critical Perspectives on Black Independant Cinema (Cambridge: MIT Press).

Chambers, Iain (1994.), Migrancy, Culture and Identity (London,: Routledge).

Chamot, A (1988), ‘Bilingualism in Education and Bilingual Education: the State of the Art in the United States’, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, (9), 11-35.

Chandhoke, Neera (1999), Beyond secularism: the rights of religious minorities (Delhi: Oxford University Press).

Chapdelaine, J.-P. (2010), ‘La corédaction des textes législatifs comme laboratoire de la culture juridique et linguistique au Canada’, paper given at “Language, Law and the Multilingual State” 12th International Conference of the International Academy of Linguistic Law Bloemfontein, 1-3 november 2010.

— (2012), ‘Official Languages Act (Ireland) 2003: a review to row back rights and institutional obligations’, in Fernand De Varennes (ed.), Droits Linguistiques, inclusion et la prévention des conflits ethniques (Chiang Mai).

Chatterjee, Partha. . (1994), ‘Secularism and toleration’, Economic and Political Weekly, 28 ( 29), 1768-77.

Chaudenson, Robert and Robillard (de), Didier (1990), Langues, Economie et Développement (Aix-Marseille: Institut d’Etudes Créoles et Francophones, Université de Provence).

Chavez, Lydia (1998), The Color Bind (Berkeley: University of California Bress) 305.

Chayes, Abram and Handler Chayes, Antonia (1998), The New Souvereinty (Cambridge, Massachussetts: Harvard University Press).

Chemla, David (ed.), (2011), JCall: les raisons d’un appel (Paris: Liana Levi ) 126.

— (2011), ‘Préface: l’âge de raison’, in David Chemla (ed.), JCall: les raisons d’un appel (Paris: Liana Levi ), 11-18.

— (2011), ‘Pour que ces deux rêves deviennent mutuels: entretien avec Daniel Cohn-Bendit’, in David Chemla (ed.), JCall: les raisons d’un appel (Paris: Liana Levi ), 37-48.

— (2011), ‘Pour l’amour d’Israël, Entretien avec Bernard-Henry Lévy’, in David Chemla (ed.), JCall: les raisons d’un appel (Paris: Liana Levi ), 67-86.

— (2011), ‘Mon inquiétude: l’avenir d’Israël, Entretien avec Dominique Schnapper’, in David Chemla (ed.), JCall: les raisons d’un appel (Paris: Liana Levi ), 97-104.

— (2011), ‘Gardons-nous de nous laisser entraîner dans le refus de l’autre, Entretien avec Michel Serfaty’, in David Chemla (ed.), JCall: les raisons d’un appel (Paris: Liana Levi ), 105-16.

— (ed.), (2011), Les raisons d’un appel: JCall, appel à la raison des Juifs européens., ed. David Chemla (JCall: les raisons d’un appel, Paris: Liana Levi ) 11-18.

Chemla, David, et al. (2012), ‘Changing Paradigms Among World Jewry for a Two-State Solution’, J Street: Making History (Washington D.C.).

Cherruau, Pierre (2001), ‘Luc Lagouche: Dans le club qu’il a créé à Kano, au Nigéria, il s’obstine à faire jouer ensemble musulmans et chrétiens, alors que règne la charia’, Télérama, (2662), 40-41.

Cheshire, J. (1991), English Around the World: Sociolinguistic Perspectives (Cambridge,: Cambridge University Press,).

Cheshire, Jenny (2011), ‘Adolescents as linguistic innovators: dialect contact and language contact in present-day London’, paper given at Langues en contact: le français à travers le monde, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 16-18 septembre 2011.

Chevallier, Anne-Claire (2000), ‘Francophones’, Télérama, (2659), 6.

Chiswick, B. (ed.), (1992), Immigration, Language and Ethnicity (Washington D.C.: The AEI Press).

Chomsky, Noam and Halle, Morris (1968), The Sound Pattern of English (New York: Harper and Row).

Chomsky, Noam (1977), Dialogue avec Mitsou Ronat (Paris: Flamarion).

— (2000), ‘Al-Aqsa Intifada’, Al-Ahram Weekly On-line, (506).

Chrétien, Jean (1997), ‘Prime Minister to Host 5th APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting in Ottawa, Ontario’, (e-mail).

— (1997), ‘APEC CEO Summit Opening Ceremony Keynote Address, Vancouver, British Columbia’, (e-mail).

Chumbow, B. S. (2010), ‘Towards a legal framework for language charters in Africa. ‘ paper given at “Language, Law and the Multilingual State” 12th International Conference of the International Academy of Linguistic Law Bloemfontein, 1-3 november 2010.

Churchill, S (1986), The Education of Linguistic and Cultural Minorities in OECD Countries (Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters).

Cinquin, Chantal (1989), ‘President Mitterand Also Watches Dallas: American Mass Media and French National Policy’, in Roger Rollin (ed.), The Americanization of the Global Village: Essays in Comparative popular Culture (Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Popular Press), 12-23.

Clark, Gordon L. , Forbes, Dean, and Francis, Roderic (eds.) (1993.), Multiculturalism, Difference and Postmodernism 1 vols. (1ère edn., 1; Melbourne: Longman Cheshire) 175.

Clarke, T and Galligan, B. J. (1995), ”Aboriginal Native’ and the Institutional Construction of the Australian Citizen 1901-48.’ Australian Historical Studies, 26 (105), 523-43.

Clarkson, Adrienne (1999), ‘Exerpts from her adress on Thursday Oct.7, 1999: to be complex does not mean to be fragmented” – At her installation yesterday, Canada’s new Governor-General spoke of “the paradox and the genius of our Canadian civilization”‘, The Globe and Mail, Friday, Oct. 8, 1999, p. A11.

— (1999), ‘Governor’s General Address’, The Globe and Mail, Friday, October 8, 1999, p. A11.

Claude, Patrice (2000), ‘Et si un ou une papiste montait bientôt sur le trône d’Angleterre’, Le Monde, Mercredi 1er Novembre 2000, p. 1.

Clément, Catherine (2006), Qu’est-ce qu’un peuple premier ? (Paris: Ed. du Panama).

Cloonan, J.D. and Strine, J.M. (1991), ‘Federalism and the development of language policy: preliminary investigations’, Language Problems and Language Planning, (15.3), 268-81.

Cloud, N., Genesee, F, and Hamayan, E. (2000), Dual Language Instruction: A handbook of enriched education (Boston: Heinle & Heinle).

Clyne, M.G (1985), Multilingual Australia: Resources, Needs, Policies., 1 vols. (2ème edn., 1; Burnley, VIC: Monash University Press) 181.

Clyne, Michael, G (1992), Community Languages in Australia (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Clyne, Michael G.., in , vol. , No. , april 1997. (1997), ‘Language policy in Australia: achievements, disappointments, prospects’, Journal of Intercultural Studies, 18 (1), 63-71.

Cobarrubias, J. and J., Fishman (eds.) (1983), Progress in Language Planning, International Perspectives (Berlin: Mouton).

Cole, Michael and Bruner, Jerome S (1972), ‘Cultural differences and inferences about psychological processes’, American Psychologist, (26), 867-76.

Colombo, Jean Robert (ed.), (1991), The Dictionary of Canadian Quotations (René Lévesque) (Toronto: Stoddart).

Combes, Mary Carol (1992), ‘English Plus: Responding to English Only’, in James Crawford (ed.), Language Loyalties: A source-book on the Official English ControversyCrawford, James (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press), 216-24.

Combesque, Agnès (1999), ‘Comme des papillons vers la lumière’, Le Monde Diplomatique, (Décembre 1999), 16 et 17.

Commissaire, aux Langues Officielles (1990), ‘Rapport Annuel 1989’, (Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles).

— (1991), ‘Rapport Annuel 1990’, (Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles).

— (1992), ‘Rapport Annuel 1991’, (Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles).

— (1993), ‘Rapport Annuel 1992’, (Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles).

— (1994), ‘Rapport Annuel 1993’, (Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles).

— (1995), ‘Rapport Annuel 1994’, (Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles).

— (1996), ‘Rapport Annuel 1995’, (Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles).

— (1997), ‘Rapport Annuel 1996’, (Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles).

Commission, Aboriginal Lands Rights (1973), ‘First Report’, (Canberra: Australian Parliament).

— (1974), ‘First Report’, (Canberra: Australian Parliament).

Commission (1991), ‘Human Rights and Equal Oppportunity Commission’.

Commonwealth (1984), ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984’, (Canberra: Commonwealth).

Conley, John M. and O’Barr, William (1998), Just Words: Law, Language and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 168.

Conseil, de l’Europe (1991), ‘Europe 1990-2000: Multiculture dans la Cité, l’Intégration des immigrés’, Conférence permanente des pouvoirs locaux et régionaux de l’Europe (1; Francfort-sur-le-Main: Les Editions du Conseil de l’Europe).

Conseil, de l’Europe (1992), ‘Charte européenne des langues régionales ou minoritaires’.

Conseil, de l’Europe (2001), ‘Cadre européen commun de référence pour les langues: apprendre, enseigner, évaluer’, (Didier).

Cook, Ramsay (1986), Canada, Québec and the uses of Nationalism (2ème edn.; Toronto: McClelland & Stewart).

Cooper, R.L. (1989), Language Planning and Social Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Coronel Molina, Serafin (2012), ‘Indigenous Languages as Cosmopolitan and Global Languages: The Latin American Case’, paper given at Languages in the City, Berlin, 21-24 August, 2012.

Correa da Costa, Sergio (1999), Mots sans Frontières (Paris: Editions du Rocher).

Corrigan, Tim (1991), A Cinema Without Walls: Movies and Culture After Vietnam (London: Routledge).

Corson, D and Lemay, S (1996), Social Justice and Language Policy in Education: The Canadian Research (Toronto: OISE Press) 149–68.

Corson, David (1997), ‘Social Justice in the Work of ESL Teachers’, in William Eggington and Helen Wren (eds.), Language Policy: Dominant English, pluralist challenges (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 149–68.

Cortanze (de), Gérard (2002), Assam (Paris: Albin Michel) 537.

Coulmas, Florian (1991), ‘The Language Trade in the Asian Pacific’, Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 2, 1-27.

— (1992), Language and Economy (Oxford: Basil Blackwell).

Courtney, John C. (1996), Do Conventions Matter? : Choosing National Party Leaders in Canada (McGill Queens University Press) 477 pages.

Craven, I. (ed.), (1994), Australian Popular Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Crawford, James (ed.), (1988), The Rights of Peoples (Oxford: Clarendon Press) 236.

— (1989), Bilingual Education: History, Politics, Theory and Practice (Trenton, New Jersey: Crane Publishing).

— (1992), Hold your Tongue (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company) 324.

— (1992), Language Loyalties: A Sourcebook on the Official English Controversy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 522.

Creel, George (1947), Rebel at Large: Recollections of Fifty Crowded Years (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons) pp. 198-99.

Crépeau, François, Fournier, Stéphanie, and Néel, Lison (eds.) (1991), Séminaire International de Montréal sur l’Education Interculturelle et Multiculturelle 1 vols. (Numéro Spécial, 12; Montréal: Société Québécoise de Droit International) 273.

Crépon, Marc (2000), Le Malin Génie des langues (Paris: J. Vrin) 224.

Crowley, Terry (1998), An Introduction to Historical Linguistics (3d edn.; Oxford: Oxford University Press) 342.

Crystal, David (1995), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of English Language (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 489.

— (1997), English as a Global Language (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 150.

Cubertafond, Bernard (1995), L’Algérie contemporaine (Que SaisJe?; Paris: PUF).

Culhane, J.G. (1992), ‘Reinvigorating Educational Malpractice Claims: A Representational Focus”‘, Washington Law Review, 2 (67), 349-414.

Cumming, Alister (1997), ‘English Language-in-Education Policies in Canada’, in William Eggington and Helen Wren (eds.), Language Policy: Dominant English, pluralist challenges (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 91-105.

Cummins, J. (ed.), (1984), Heritage languages in Canada: Research Perspectives (Toronto: OISE Press).

— (1989), ‘Heritage language teaching and the ESL student: fact and friction’, in J. Esling (ed.), Multicultural Education and Policies: ESL in the 1990s (Toronto: OISE Press), 3.17.

Cunningham, S. (1992), Framing Culture: Criticism and Policy in Australia (Sydney: Allen & Unwin).

CURANT, NIKOLAS ‘addition to Sociolinguists on FB Award’.

Cusin, Philippe (1999), ‘Abd el-Krim, le Mythe du Rebelle’, Le Figaro Littéraire, 12 aout, p. 3 (17).

Dafoe, J.W. (1935), Canada: An American Nation (New York: Columbia University Press).

Dakhli, Leyla (2009), ‘Le multilinguisme est un humanisme’, La Vie des Idées, <http://www.laviedesidees.fr/Le-multilinguisme-est-un-humanisme.html>, accessed 4.11.2009.

Dakhlia, Jocelyne (2008. ), Lingua Franca. Histoire d’une langue partagée en Méditerranée (Actes Sud).

Dalby, David (1969), ‘Patterns of Communication in Africa and the New World’, (Hans Wolff Memorial Lecture).

Daniel, Dominique (1996), L’immigration aux Etats-Unis (1965-1995): Le poids de la réunification familiale (Le Monde Nord-Américain; Paris et Montréal: L’Harmattan (Inc,)) 236.

Daniel, Jean- (2009), ‘Camus, le sacre’, Le Nouvel Obs, 1.

Daniels, H.A. (ed.), (1990), Not Only English: Affirming America’s Multilingual Heritage (Urbana, Ilinois: National Council of Teachers of English).

Danley, John (1991), ‘ Liberalism, aboriginal rights and cultural minorities’, ‘Philosophy and Public Affairs, 2 (20), 168-85.

Daoud, Zakya (1999), Abdelkirm, une épopée d’or et de sang (Paris: Séguier).

Das Gupta, Jyotirindra (1970), Language conflict and national development: group politics and national policy (Bombay: Oxford University Press).

Dasgupta, Probal (2012), ‘La politique linguistique et les langues indiennes moins répandues’, Droit et Cultures, 63 (S’entendre sur la langue), 127-44.

Dawkins, J.S. (1988), ‘Challenges and Opportunities: our future in Asia’, in E.M. McKay, Asian Studies Association of Australia (ed.), Challenges and Opportunities: our future in Asia (Melbourne: Morphett Press), 13-21.

de Certeau, Michel, Julia, Dominique, and Revel, Jacques (2002), Une Politique de la langue: la révolution française et les patois: l’enquête de l’Abbé Grégoire (Paris: Editions Gallimard) 472.

de Cortanze, Gérard (1998), Les Vice-Rois (Arles: Actes Sud) 669.

de Swaan, Abram (2001), Words of the World (Cambridge: Polity Press,).

— (2005), ‘Utiliser l’instrument de l’anglais sans se noyer dans sa culture.’ Le Temps, 13 septembre 2005.

De Varennes, Fernand (1996), Language, Minorities and Human Rights (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers).

— (1999), ‘Les droits de l’homme et la protection des minorités linguistiques’, in Hervé Guillorel and Geneviève Kouby (eds.), Langues et Droit: Langues du droit, droit des langues (Bruxelles: Bruylant), 129-41.

— (2010), ‘Closing Keynote.’ paper given at “Language, Law and the Multilingual State” 12th International Conference of the International Academy of Linguistic Law Bloemfontein, 1-3 november 2010.

— (2010), ‘One people, One language? The response of International law to the multilingual state. ‘ paper given at “Language, Law and the Multilingual State” 12th International Conference of the International Academy of Linguistic Law Bloemfontein, 1-3 november 2010.

— (2012), ‘Langues officielles versus droit linguistiques: L’un exclut-il l’autre?’ Droit et Cultures, 63 (S’entendre sur la langue), 33-50.

De Vries, John (1985), ‘Some methodological aspects of self report questions on language and ethnicity’, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 6, 347-68.

Debray, Régis (2000), ‘Sus aux Clochers! La nation n’a plus besoin de hussards: Ce n’est pas une raison pour la réduire à une France du chacun pour soi, où les racines prennent le pas sur les valeurs.’ L’Express, (2558), 58-59.

Decraene, Philippe (1981), ‘Interview d’Amadou Hampate Ba’, in Jacques Meunier (ed.), Entretiens avec Le Monde (4; Paris: Editions La Découverte/ Le Monde), 169-83.

DEET (1991), ‘Australia’s Language: The Australian Language and Literacy Policy’, (Canberra: Department of Employment, Education and Training).

Déguinet, Jean-Marie (1999), Mémoires d’un Paysan Bas-Breton, trans. Bernez Roux (14 edn.; Ar Releg-Kerhuon: An Here).

Delafenêtre, David G. (1997), ‘Interculturalism, Multiracialism and Transculturalism: Australian and Canadian Experiences with Multiculturalism and Its Alternatives in the 1990s’, Nationalism & Ethnic Politics, ( 3.1).

Delbecq, Denis (1998), ‘UNL, un nouvel Esperanto pour le Web’, Le Monde Interactif, (Samedi 5 Décembre 1998).

Dempsey, Hugh (1986), ‘The Blackfoot Indians’, in B. Morrison and Wilson R. (eds.), Native Peoples: the Canadian Experience (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart), 381-413.

Denutte, Alexandre (1994), ‘L’enseignement immersif au Canada et ses applications’, Dir. M.P. Gautier (Paris 4 Sorbonne).

Dervez, Luis (2012), ‘Keynote Address’, in Interdependence Day (ed.), (Los Angeles: Benjamin Barber).

Descola, Philippe (1996), ‘Commentaires sur l’écriture de l’ouvrage Les lances du Crépuscule.’ (Troisième cycle Romand de Sociologie).

Détienne, Marcel (2000), Comparer l’incomparable (« Libairie du XXIe siècle »; Seuil ).

Deumert, Ana and Klein, Yolandi (2012), ‘Marginal Diversities and Digital Conormities: the strudture of Multilingua performances’, paper given at Languages in the City, Berlin, 21-24 August, 2012.

Deutsch, Martin (1967), The disadvantaged child (New York: Basic Books).

Devonish, Hubert (2012), ‘Stop Demonising Patois -From A Semi-Lingual To A Bilingual Jamaica’, The Gleaner, 26 Aug.

Dewey, J.L. (1938), Experience and Education (New York: Ramdom House).

Diawara, Manthia (ed.), (1993), Black American Cinema (New York: Routledge).

Dieckhoff, Alain (2000), La nation dans tous ses Etats: les identités nationales en mouvement (Paris: Flammarion).

Dillard, J.L. (1972), Black English: its History and Usage in the United States (New York: Random House).

— (1972), A History of American English (New York: Longman).

Dion, Stéphane (1991), ‘Le Nationalisme dans la Convergence Culturelle’, in R. Hudon and R. Pelletier (eds.), L’Engagement Intellectuel (Sainte-Foy: Les Presses de l’Université Laval,).

— (1994), ‘ Le fédéralisme fortement asymétrique: improbable et indésirable’, in F.L. Seidle (ed.), A la Recherche d’un nouveau Contrat politique pour le Canada: Options asymétriques et options confédérales (Québec: Institute for Research on Public Policy), 133-52.

Djérad, Najoua (2012), ‘Conflits linguistiques dans les pays linguistiques au Maghreb’, in Fernand De Varennes (ed.), Droits Linguistiques, inclusion et la prévention des conflits ethniques (Chiang Mai).

Djité, Paulin (1994), ‘From Language Policy to Language Planning: An Overview of Languages other than English in Australian Education.’ (The National Language and Literacy Institute of Australia).

Doecke, B (1993), Kookaburras, blue gums, and ideological state apparatuses: English in Australia.

Donnelly, J. (2003), Universal Human Rights in Theory and Practice (New York: Cornell University Press).

Doucet, Michel (2012), ‘Etat linguistique’, in Fernand De Varennes (ed.), Droits Linguistiques, inclusion et la prévention des conflits ethniques (Chiang Mai).

Douzinas, C. (2000), The End of Human Rights (Oxford: Hart).

Draper, Jamie B (1991), ‘Dreams, Realities, and Nightmares: The present and Future of Foreign Language Education in the United States’, (Washington: Joint National Committee for Languages in cooperation with the National Council of State Supervisors of Foreign Languages).

Draper, Jamie B and Martha, Jiménez (1992), ‘A chronology of the Official English Movement’, in James Crawford (ed.), Language Loyalties: A source-book on the Official English Controversy (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press), 89-94.

Draper, John (2009), ‘ Moves towards meeting international treaty obligations regarding multilingual education in Thailand’, paper given at International Conference on Educational Research, Khon Kaen, Thailand, 11 September.

— (2012), ‘Reconsidering compulsory English in developing countries in Asia: English in a Community of Northeast Thailand’, TESOL Quarterly, 46 (4), 777-811.

— (2012), ‘Revisiting English in Thailand’, Asian EFL Journal., 14 (4), 9-38.

Druke Becker, Martine (1986), ‘Iroquois and Iroquoian in Canda’, in B. Morrison and Wilson R. (eds.), Native Peoples: the Canadian Experience (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart), 323-46.

Du Plessis, Theodorous (2010), A language Act for South Africa? The role of sociolinguistic principles in the analysis of the language legislation.

Dua, Hans Raj (1996), ‘The Politics of Language Conflict: Implications for Language Planning and Political Theory’, Language Problems and Language Planning, 1-17.

DuBois, W and E.Burghardt (1896), The Suppression of African Slave Trade in the United States of America 1638-1870.

DuBois, W.E.Burghardt (1961), (1903) The Souls of Black Folk (Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Publications Inc.).

Ducrot, Osward and Todorov, Tzvetan (1972), Dictionnaire encyclopédique des sciences du langage (Points Essais, 110; Paris: Editions du Seuil) 470.

Dufour, Christian (1989), Le Défi Québécois (Montreal: L’Hexagone).

Dumont, Fernand (1997), Raisons communes (Compact; Beauceville: Boréal) 261.

Durand, Jorge (1996), Migrations mexicaines aux Etats-Unis (Paris: CNRS Editions) 214.

Duranti, Alessandro (1994), From Grammar to Politics: Linguistic Anthropology in a Western Samoan Village (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Duverger, Maurice (1973), Sociologie de la Politique (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France).

Dworkin, Ronald (1983), ‘ In defense of equality’, Social Philosophy and Policy, 1 ( 1), 24-40.

Dworkin, R. (2005), Taking Rights Seriously (London: Duckworth).

Earlie, James (2012), ‘Transnational lives’, Interdependence Day 2012 (Los Angeles: Benjamin Barber).

Eastman, Carol (1993), Language Planning: an Introduction (San Francisco: Chandler & Sharp).

Eckermann, Ann-Katrin (1994), One Classroom, Many Cultures: Teaching Strategies for Culturally Different Children (St Leonards, Nouvelle Galles du Sud, Australie: Allen & Unwin).

Eckert, Penelope ‘suites de sa biblio’.

Eckert, Penelope (2008), ‘theory of social style and the indexical field.

‘ Journal of Sociolinguistics/, 2008: , 12 (4), 453-76.

Eco, Umberto ( 1994), La Recherche de la langue Parfaite, (Paris: Editions du Seuil).

Edwards, John (1984), Linguistic Minorities, Policies and Pluralism (London: Harcourt Brace).

Edwards, J., Language (1985), Language, Society and Identity (Oxford: Basil Blackwell).

Edwards, J. (1994), Multilingualism (1 edn.; London: Routledge) 256.

Eftiemi, Alexandra

Macovei, Oana (2012), ‘Protection des locuteurs et protection des langues minoritaires ou régionales en Roumanie’, Droit et Cultures, 63 (S’entendre sur la langue), 145-70.

Eggington, William and Wren, Helen (eds.) (1997), Language Policy: Dominant English, pluralist challenges (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company) 170.

Eggington, William (1997), ‘The English Language Metaphors We Plan By.’ in William Eggington and Helen Wren (eds.), Language Policy: Dominant English, pluralist challenges (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 29-46.

Eisenberg, Avigail (1994), ‘The Politics of Individual and Group Difference in Canadian Jurisprudence’, Canadian Journal of Political Science, (27), 3-21.

Eisner, Jane (2012), ‘keynote’, J Street, Making History (Washington DC).

El Mountassir, Abdallah (2012), ‘Droits linguistiques et inclusion sociale des communautés amazighes: exemple de la communauté amazighe du Maroc’, in Fernand De Varennes (ed.), Droits Linguistiques, inclusion et la prévention des conflits ethniques (Chiang Mai).

Elliot, Michael (1998), ‘A letter to the French: we don’t think that France is a nightmare; we just think it should be more like Holland’, Newsweek, CXXXI (25), 2.

Elliott, Jean Leonard (1985), Two Nations, Many Cultures: Ethnic Goups in Canada (Carborough, Ont.: Prentice Hall).

Ellis, Rod (1999), Second Language Acquisition (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

El-Mekkaoui, Fatima (1997), ‘Problèmes d’Immigration aux Etats-Unis d’Amérique entre 1900 et 1926’, (Sorbonne).

Eloy, J.-M. (2010), ‘Aménagement, politique, droits linguistiques: de la pertinence de ces notions dans le cas de la France’, paper given at “Language, Law and the Multilingual State” 12th International Conference of the International Academy of Linguistic Law Bloemfontein, 1-3 november 2010.

Epp, Charles R. (1998), The Rights Revolution: Lawyers, Activists and Supreme Courts in Comparative Perspectives (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press) 326.

European Centre on Migration and interethnic relations.

Esling, J. (ed.), (1989), Multicultural Education and Policies: ESL in the 1990s (Toronto: OISE Press).

Espéranto, Association Mondiale de l’ (2003), ‘L’égalité des langues: une nécessité pour l’Europe’, Le Monde, 14 juin, p. 5.

Estrada, Marcos (2012), ‘Universal Vision and Philosophical Framework’, in Surendra Pathak (ed.), Teacher Education for Peace and Harmony (New Delhi and Shardarsahar).

Eugenides, Jeffrey (2003), Middlesex (2nd edn.; London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc) 529.

Ewers, Traute (1996), The Origin of American Black English: Be-Forms in the HOODOO Texts (Berlin and New York: Mouton).

Fairclough, N. (1985), Language and Power (New York: Longman Publishing).

Falcoff, Mark (1996), ‘article’, Times Literary Supplement.

Falk, Richard (1988), ‘The Rights of Peoples (In Particular Indigenous People)’, in James Crawford (ed.), The Rights of Peoples (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 17-37.

Farhat, Mokhtar (2011), ‘L’interlangue et les interférences linguistiques: anaylyse d’un corpus de production écrite dans les classes de français en Tunisie’, paper given at Langues en contact: le français à travers le monde, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 16-18 septembre 2011.

Faries, E (1989), ‘Language Education for Native Children in Northern Ontario’, in J. Esling (ed.), Multicultural Education and Policies: ESL in the 1990s (Toronto: OISE Press), 144-53.

Farrar, Arihia (2011), ‘He Taonga te repo (title of her poem too)’, paper given at World Conference on the Education of the Indigenous People (WIPCE 2011), Cusco, Peru.

Fase, Willem, Koen, Jaspaert , and Kroon, Sjaak (eds.) (1992), Maintenance and Loss of Minority Languages (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company).

Fasold, Ralph (1969), ‘Tense and the form be in Black English’, Language, (45), 763-76.

— (1972), ‘Tense marking in Black English’, (Washington, D.C.: Center for Applied Linguistics).

— (1984), The Sociolinguistics of Society (Oxford: Basil Blackwell).

Feher, Michel (1995), ‘Identités en évolution: individu, famille, communauté aux Etats-Unis’, Esprit, (Juin 1995), 114-31.

Feliciano, Hector and Sulic, Dijana (1997), ‘Le monde se divise désormais selon les appartenances de civilisations.’ Le Nouveau Quotidien, 28 février, p. 16.

Fellows, Donald Keith (1972), A Mosaic of America’s Ethnic Minorities (New York: Wiley).

Fenet, Alain, Koubi, Geneviève, and Schulte-Tenckhoff, Isabelle (2000), Le Droit et les Minorités (2ème edn., Orgaisation internationale et relations internationales; Bruxelles: Bruylant) 661.

Ferenczi, Aurélien (2000), ‘Un Indien chez les Cow-boys’, Télérama, (2659), 20.

Ferguson, Charles .A and Brice, Heath Shriley (eds.) (1981), Language in the USA (3 edn., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 592.

Ferguson, Charles A. (1981), ‘Foreword’, in Braj B. Kachru (ed.), Pergamon Institute of English (Oxford: Pergamon Press), vii-xi.

Fesl, Eve (1991), ‘A Koorie View’, in D. Goodman, D.J. O’Hearn, and C. Wallace-Crabbe (eds.), Multicultural Australia: the challenges of change (Melbourne: Scribe), 56-60.

Fetzer, Philip L. (ed.), (1998), The Ethnic Moment: the search for equality in the American Experience (Armonk, N.Y., London, U.K.: M.E. Sharpe) 269.

Emission Répliques du 24 février 2007: L’héritage de Pierre Mendès France (2007) (émission radiophonique, France Culture).

Emission Répliques du 29 Septembre 2012: Faut-il déconstruire Israel (2007) (émission radiophonique, France Culture).

Finkielkraut, Alain (2011), ‘Les yeux ouverts’, in David Chemla (ed.), JCall: les raisons d’un appel (Paris: Liana Levi ), 49-53.

Emission Répliques du octobre 2012: La création du Monde (2012) (émission radiophonique, France Culture).

Finney, Angus (1996), The State of European Cinema: A New Dose of Reality (London: Cassell).

Fishman, Joshua A. and Nahirny, Vladimir C. (1966), ‘Organization and leadership in language maintenance’, in Fishman (ed.), Language Loyalty in the United States, 156-89.

Fishman, Joshua A. (1967), ‘Bilingualism with and without diglossia: Diglossia with and without Bilingualism’, Journal of Social Issues, (23), 29-38.

— (ed.), (1968), Readings in the sociology of language (The Hague: Mouton).

Fishman, Joshua A. and Dillard, JL. (1975), Perspectives on Black English (The Hague: Mouton).

Fishman, Joshua A. , et al. (1985), The Rise and Fall of Ethnic Revival (Contributions to the Sociology of Language, 37; Berlin, New York et Amsterdam: Mouton) 531.

Fishman, Joshua A. (1992), ‘The Displaced Anxieties of Anglo-Americans’, in James Crawford (ed.), Language Loyalties: A source-book on the Official English Controversy (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press), 165-67.

— (2012), ‘Etats du Yiddish: les différents types de reconnaissance gouvernementale ou non gouvernementale (Varieties of Governement and Non-Governement recognition of Yiddish’, Droit et Cultures, 63 (S’entendre sur la langue), 23-32.

Fitzgerald, Frances (1980), America Revised (New York: Vintage Books).

FitzGerald, Stephen (1997), Is Australia an Asian Country ? (St Leonards: Allen & Unwin).

Flaysakier, Jean-Daniel (2002), ‘Télescopage’, Libération, 22 avril 2002, p. 17.

Fleras, Augie and Elliott, Jean Leonard (1992), The Nation within: Aboriginal State Relations in Canada, the United States and New Zealand (Toronto: Oxford University Press).

Foucher, P. (2010), ‘les droits linguistiques et la jurisprudence canadienne. ‘ paper given at “Language, Law and the Multilingual State” 12th International Conference of the International Academy of Linguistic Law Bloemfontein, 1-3 november 2010.

Foucher, Pierre (2012), ‘Official Languages Act (Ireland) 2003: a review to row back rights and institutional obligations’, in Fernand De Varennes (ed.), Droits Linguistiques, inclusion et la prévention des conflits ethniques (Chiang Mai).

Franklin, Benjamin (1961), ‘Observations concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries Etc.’ in Leonard W. Labaree (ed.), Papers (4; New Haven: Yale University Press).

Fraser, Graham and McIlroy, Anne (1999), ‘Clinton buoys federal cause’, Globe and Mail, October 9, 1999, p. A1.

Fraser, N. (2001), ‘‘Recognition Without Ethics’, Theory Culture and Society, (18), 21-42.

Fredrik, Barth (1995), ‘Les Groupes ethniques et leurs frontières’, in Philippe Poutignat and Jocelyne Streiff-Fenart (eds.), Théories de l’Ethnicité (1ère edn., 1; Paris: Presses Universitaires de France), 270.

Frideres, James (1997), ‘Edging into the Mainstream: Immigrant Adult and their Children’, in S. Isajiw (ed.), Comparative Perspectives on Interethnic Relations and Social Incorporation in Europe and North America (Toronto: Canadian Scholar’s Press), 537-62.

Friedman, Thomas L. (2012), ‘Power with Purpose’, Herald Tribune, 24 May 2012.

Fyfe, Christopher (ed.), (1991), Our Children Free and Happy”: Letters from Black Settlers in Africa in the 1790s. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press).

Gabizon, Cécilia (2001), ‘A TOULOUSE, LES FILS DU VENT SE SEDENTARISENT’, Le Figaro, 10 septembre 2001, p. 12.

Gabler, Neal (1988), An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood (New York: Crown).

Gadet, Françoise and Ludwigh, Ralph (2011), ‘synthèse finale et clôture du colloque.’ paper given at Langues en contact: le français à travers le monde, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 16-18 septembre 2011.

Gagnon, Paul (1989), Democracy’s untold Story: What American History Textbooks should Add. (Washington, D.C.: American Federation of Teachers).

Galenkamp, Marlies (1993), Individualism and collectivism: the concept of collective rights (Rotterdam: Rotterdamse Filosofische Studies).

Galindo-Anze, Eudoro (1999), ‘Immigration Centennial Ehances Close Relations’, The Japan Times, Aug.6, p. 5.

Gamston, William A. (2012), ‘Arab Spring, Israeli Summer, and the Process of Cognitive Liberatoin’, Swiss Political Science Review : , 17 (4), 463-68.

Blacklash?Black facts Web Page (1996) (Web page).

Gauld, Greg (1992), ‘Multiculturalism, the real thing?’ in Stella Hryniuk (ed.), Twenty Years of Multiculturalism: Successes and Failures (Winnipeg: St John’s College Press), 9-16.

Gautier, Maurice-Paul (ed.), (1992), Hommage à Maurice-Paul Gautier, Regards Européens sur le Monde Anglo-Américain (Paris: Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne,).

— (1995), ‘Langues vivantes et temps présent’, Comprendre les langues aujourd’hui. (Dijon: Tribune Internationale des Langues Vivantes).

Gellner (1983), Nations and Nationalism (Oxford: Basil Blackwell).

Gerard, Jean B. (1984), ‘Pourquoi les Etats-Unis ont du quitté l’UNESCO’, Revue des deux Mondes, (Juin).

Germon, Marie-Laure (2004), ‘l’identité par la langue’, Le Figaro.

Gibbs, Jonathan W. (1994), ‘The use of words: How so-called foul words can have many meanings’, (The City College: The City University of New York term paper for course on African-American English).

Giesbert, Franz-Olivier (2012), ‘La fin d’une époque’, Le Point, 20 septembre 2012, sec. Editorial p. 7.

Giglioli, P.P. (1972), Language and Social Context (London: Penguin Books).

Gillespie, M. (1995), Television, Ethnicity and Cultural Change (London: Routledge).

Giordan, Henri (1992), ‘Les Langues Minoritaires, Patrimoine de l’Humanité’, in Hervé Guillorel and Jean Sibille (eds.), Langues, dialectes et écriture (Paris: Institut d’Etudes Occitanes et Institut de Politique Internationale et Européenne), 173-85.

Gitlin, Todd (1992), ‘On the Virtues of Loose Canon’, in Paul Berman (ed.), Debating PC: The Controversy over Political Correctness on College Campuses (New York: Laurel).

Glazer, Nathan and Moynihan, Daniel P. (1963), Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians and Irish of New York City (Cambridge: MIT Press).

Glazer, Nathan (1975 (1987)), Affirmative Discrimination (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

— (1995), ‘Individual Rights against Group Rights’, in Will Kymlicka (ed.), The Rights of Minority Cultures (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 387.

— (1997), We are all Multiculturalists Now (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

Godbout, Jacques (1989), ‘(à propos de Montréal)’, Globe and Mail.

Godreche, Dominique (1999), ‘FESTIVAL DE DOUARNENEZ : Le Yiddishland au cinéma’, LE MONDE DIPLOMATIQUE, (AOÛT), 19.

Gohard, Aline (1997), ‘D’une multiculturalité reconnue vers un plurilinguisme construit’, in Peter Lang (ed.), Multilinguisme et Multiculturalité (Fribourg: Peter Lang).

— (1997), ‘Publics spécifiques: quels enjeux ? quelles démarches? pour quels nouveaux besoins’, Revue de Linguistique et de Didactique des langues (LIDIL), 16 (dec.1997).

— (1998), ‘Peut-on former à l’interculturel? quels concepts et quelles démarches’, Bulletin de l’Association pour la recherche interculturelle (ARIC), (30).

— (1999), Communiquer en langue étrangère. Des compétences culturelles vers des compétences linguistiques. (Bern: Peter Lang).

Gold, Robert (1960), A Jazz Lexicon (New York: Knopf).

Gold, David (1987), ‘The speech and writing of Jews’, in Charles A. Ferguson and Shirley Brice Heath (eds.), Language in the USA (1; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 273-92.

Goldberg, D.T. (ed.), (1994), Multiculturalism: a critical reader (Oxford: Blackwell).

Goodman, D., O’Hearn, D.J., and Wallace-Crabbe, C. (eds.) (1991), Multicultural Australia (Melbourne: Scribe).

Gordon, Milton (1964), Assimilation in American life: the role of race, religion and national origin (New York: Oxford University Pres).

Görlach, Manfred (1997), ‘Language and Nation: the concept of linguistic identity in the history of English’, English World-Wide, (18), 1-34.

Gorter, Durk , Marten, Heiko F., and Van Mense, Luk (eds.) (2012), Minority Languages in the Linguistic Landscape

Edited by (Palgrave Studies in Minority Languages and Communities, London: Palgrave Macmillan).

Goudsblom, J. (1980), Nihilism and Culture (Oxford: Basil Blackwell).

Gour (Gur), Batya (1994), Meurtre à l’Université: un crime littéraire, trans. Jacqueline Carnaud et Jacqueline Lahana (Paris: Arthème Fayard) 350.

— (1995), Meurtre au Kibboutz trans. Rosie Pinhas-Delpuech (Paris: Arthème Fayard) 435.

Gouvernement, Fédéral Canadien (1867), ‘Constitution Act’.

— (1982), ‘Charte Canadienne des Droits et Libertés’.

— (1987), ‘Accord constitutionnel’.

— (1991), ‘Shaping Canada’s Future Together (Proposals )’, (Ottawa: Supply and Services).

— (1991), ‘Shared Values: The Canadian Identity’, (Ottawa: Supply and Services).

— (1992), ‘LES ACCORDS DE CHARLOTTEVILLE: Consensus Report On The Constitution Charlottetown’.

Gozlan, Martine (2012), ‘Israël: Le complot des faucons pour contrôler le pays’, Marianne.

Green, Leslie. (1994), ‘‘International minorities and their rights Group rights’, in Judith Baker (ed.), (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Green, Leslie (1995), ‘Internal Minorities and their Rights’, in Will Kymlicka (ed.), The Rights of Minority Cultures (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 387.

Grin, François (1994), ‘Combining Immigrant and Autochthonous language rights’, in Tove Skuttnab-Kangas and Robert Phillipson (eds.), Linguistic Human Rights: Overcoming Linguistic Discrimination (1; Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter), 39:70.

— (1996), ‘Economic approaches to language and language planning: an introduction’, International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 121 (1996).

Grin, François and Vaillancourt, François (1999), ‘The cost-effectiveness evaluation of minority language policies’, (Flensbourg: European Centre for Minority Issues).

Grin, François (2001), ‘Kalmykia, victim of Stalinist genocide: from oblivion to reassertion’, Journal of Genocide Research, 3 (1), 97-116.

Grin, François and Vaillancourt, François (2002), ‘Minority Self-Governance in Economic Perspective’, in Kinga Gal (ed.), Minority Governance in Europe (Flensbourg: European Centre for Minority Issues).

Grin, François and Schwob, Irene (2002), ‘Bilingual Education and Linguistic Governance: the Swiss experience’, Intercultural Educaton, 13 (4), 409-26.

Grin, François, Rossiaud, Jean, and Kaya, Bülent (2003), ‘Les Migrations et la Suisses’, in Hans-Rudolf Wicker, Rosita Fibbi, and Werner Haug (eds.), Résultat du programme national Suisse de recherche Migrations et Relations Interculturelles (Bern: Editions Seismo et FNRS), 404-33.

Grin, François (2003), ‘Diversity as Paradigm, Analytical Device, and Policy Goal’, in Will Kymlicka and Anthony Patten (eds.), Language Rights and Political Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 169-88.

— (2003), ‘La Suisse comme non-multination’, in Michel Seymour (ed.), Etats-nations, multinations et organisations supranationales (Paris: Liber), 265-81.

— (2007), ‘Pourquoi donc apprendre l’anglais? Le point de vue des élèves’, in Daphné Romy-Masliah and Larissa Aronin (eds.), L’Anglais et les Cultures: carrefour ou frontière? (Paris: L’Harmattan), 75-95.

Grosjean, F. (1982), Life with Two Languages: An Introduction to Bilingualism (Cambridge, Massachussets: Harvard University Press).

Grossman, David (2011), ‘Ce que je connais de la guerre me donne le droit de parler de la paix’, in David Chemla (ed.), JCall: les raisons d’un appel (Paris: Liana Levi ), 55-66.

Gruenais, M.-P. (ed.), (1986), Etats de Langue (Paris: Fondation Diderot/Fondation Arthème Fayard).

Guerrero, Ed (1993), Framing Blackness (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

Guest, Edwin (1838), History of English Rhythms.

Guillaume, P., et al. (1986), Minorités et Etat (Québec et Bordeaux: Presses de l’Université Laval et Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux).

Guillorel, Hervé (1992), ‘De l’utilisation politique de la variété dialectale’, in Hervé Guillorel and Jean Sibille (eds.), Langues, dialectes et écriture (Paris: Institut d’Etudes Occitanes et Institut de Politique Internationale et Européenne), 122-34.

Guillorel, Hervé and Koubi, Geneviève (1999), Langues du droit, droit des langues (Langues et Droit; Bruxelles: Bruylant).

Gumperz, John and Hymes, Dell (1964), ‘The ethnography of Communication’, American Anthropologist, Special Publication (66), No. 6, part 2: 137-53.

Gumperz, John (1971), Language in Social Groups (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press).

Gunew, Sneja (1993), ‘Multicultural Multiplicities: US, Canada, Australia’, in David Bennett (ed.), Cultural Studies: Pluralism & Theory (2; Melbourne: Department of English, University of Melbourne), 51-65.

Gunning, Tom (1991), D.W. Griffith and the Origins of American Narrative Film: The Early Years at Biograph (Urbana: University of Illinois Press).