Links to my bibliography from A to Z:

A B C (this page) D E F G H I J K L

Last update: December 14, 2020

PART 1: Full list

- Cadart, Jacques. 1990. Institutions politiques et droit constitutionnel (Economica: Paris).

- Cain, Bruce. 1992. ”Voting rights and democratic theory: toward a colour-blind society.’ in Grofman B. and Davidson C. (ed.), Controversies in minority voting: the voting rights act in perspective ( Brookings Institution: Washington D.C.).

- Cairns, Alan. 1991. ”Constitutional change and the three equalities.’ in Ronald Watts and Douglas Brown (eds.), Options for a new Canada (University of Toronto Press: Toronto).

———. 1995. ‘Aboriginal Canadians, citizenship and constitution reconfigurations: Canadian citizenship and constitutional change ‘ in (McClelland and Stewart: Toronto). - Cajete, G., K. Nuuhiwa, and et al. 2011. “Ancestral knowledge of Sacred places.” In World Conference on the Education of the Indigenous People (WIPCE 2011). Cusco, Peru.

- Calderon, Laurence

Gilli, Charles 2015. “Silence! On tourne: l’interactivité au service de l’analyse cinématographique.” In Journée d’étude internationale EDUCATION AU CINEMA: histoire, institutions et supports didactiques. Cinémathèque de Lausanne. - Calhoun, Craig 2005. ” Cosmopolitanism and Belonging.” In 37th International Institute of Sociology Conference: Migration and Citizenship, edited by Masamichi Sasaki. Stockholm, Norra Latin, Aula 3d Floor: NYU.

- Calvet, Louis-Jean. 1993. L’Europe et ses Langues (Plon: Paris).

- Calvet, Louis-Jean. 1996. Les Politiques Linguistiques (PUF Que-Sais-Je?: Paris).

- Calvet, Louis-Jean. 2004. Essais de linguistique: la langue est-elle une invention des linguistes? (Plon: Paris).

- Calvet, L.J. 1974. Linguistique et Colonialisme

Petit Traité de Glottophagie (Bibliothèque Scientifique Payot: Paris). - ———. 1981. Les Langues Véhiculaires (PUF Que-Sais-Je?: Paris).

- Camus, Renaud. 2012. “Même pas contre: Le mariage gay, c’est trop la honte pour l’homosexualité.” In Causeur.

- Canada. 1990. Loi sur le multiculturalisme canadien, Guide à l’intention des Canadiens (Ottawa).

- Canada, Patrimoine. 1999. “10ème Rapport annuel sur l’application de la Loi sur le multiculturalisme canadien 1997-1998.” In. Ottawa: Ministère du Patrimoine canadien.

- ———. 2013. “BACKGROUNDER: Aboriginal Offenders – A Critical Situation.” In. Ottawa: Ministère du Patrimoine canadien.

- Canovan, Margaret. 1996. Nationhood and Political Theory (Edward Elgar: Cheltenham).

- Capotorti, Francesco 1979. “‘Etude des droits des personnes appartenant aux minorités ethniques, religieuses et linguistiques.” In. Centre pour les Droits de l’Homme, Genève: Sous-commission de la lutte contre les mesures discriminatoires et de la protection des minorités des Nations Unies.

- Caravedo, Rocío and Klee, Carol A. 2012. ”Migración y contacto en Lima: el pretérito perfecto en las cláusulas narrativas’, Lengua y migración / Language and Migration, 4.

- Carby V., Hazel. 1999. Cultures in Babylon (Verso: London and New York).

- Carens, Joseph. 1987. ‘Aliens and citizens: the case for open borders’, Review of Politics, 3.

- ———. 1995. “Citizenship and aboriginal self-government.” In. Ottawa: Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

- Carey, Jonathan. 2018. ‘The Africans Who Called Tudor England Home: Hundreds of Africans lived freely during the reign of Henrys VII and VIII.’, Atlas Obscura, Accessed June 5, 2020.

- Carver, Craig. 1992. ‘The Mayflower to the Model T: the development of American Eglish.’ in T.W. Machan and Scott Ch.T. (eds.), English in its Social Contexts: Essays in Historical Sociolinguistics, (Oxford University Press: Oxford).

- Casey, John W. 1998. ‘The Ebonics Controversy: Critical Perspectives on African-American Vernacular English’, The Keiai Journal of International Studies, 1: 179-214.

- Cashmore, Ellis. 1996. Dictionary of Race and Ethnic Relations (Routledge: London).

- Casier, M. , and J. Jongerden (ed.)^(eds.). 2010. Nationalisms and Politics in Turkey: Political Islam, Kemalism and the Kurdish Issue (Routledge).

- Cassen, Bernard. 2005. ‘on peut déjà se comprendre entre locuteurs de langues romanes: Des confins au centre de la galaxie’, Le Monde Diplomatique: 22.

- ———. 2005. ‘on peut déjà se comprendre entre locuteurs de langues romanes: Un monde polyglotte pour échapper à la dictature de l’anglais’, Le Monde Diplomatique: 22.

- Castellanos, Diego. 1992. ‘A Polyglot Nation.’ in, Language Loyalties: A source-book on the Official English ControversyCrawford, James (The University of Chicago Press: Chicago).

- Castile, George Pierre. 1998. To Show Heart (The University of Arizona Press: Tucson).

- Castles, Stephen. 1997. ‘Multicultural citizenship: a response to the dilemna of globalisation and national identity’, Journal of Intercultural Studies, 18.

- Castonguay, Charles. 1994. L’assimilation linguistique: mesure et évolution 1971-1986 (Publicatiosn du Québec: Sainte-Foy, Québec).

- Castro, Max J. 1992. ‘On the Curious Question of Language in Miami.’ in James Crawford (ed.), Language Loyalties: A Sourcebook on the Official English Controversy (University of Chicago Press: Chicago).

- Cham, Mbye B., and Claire Andrade-Watkins. 1988. Critical Perspectives on Black Independant Cinema (MIT Press: Cambridge).

- Chambers, Iain. 1994. Migrancy, Culture and Identity (Routledge: London,).

- Chamot, A. 1988. ‘Bilingualism in Education and Bilingual Education: the State of the Art in the United States’, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development: 11-35.

- Charbit, Denis. 2013. “Comprendre pour mieux convaincre.” In JCall trip to Israel and Palestinian Territories. Tel Aviv: JCall.

- Chatziefremidou, Katerina 2020. “Initiation à l’art Romain.” In, edited by Cours d’initiation à l’histoire générale de l’art. Paris: Le Louvre.

- Chaudenson, Robert, and Didier Robillard (de). 1990. Langues, Economie et Développement (Institut d’Etudes Créoles et Francophones, Université de Provence: Aix-Marseille).

- Chavez, Lydia. 1998. The Color Bind (University of California Bress: Berkeley).

- Chayes, Abram, and Antonia Handler Chayes. 1998. The New Souvereinty (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachussetts).

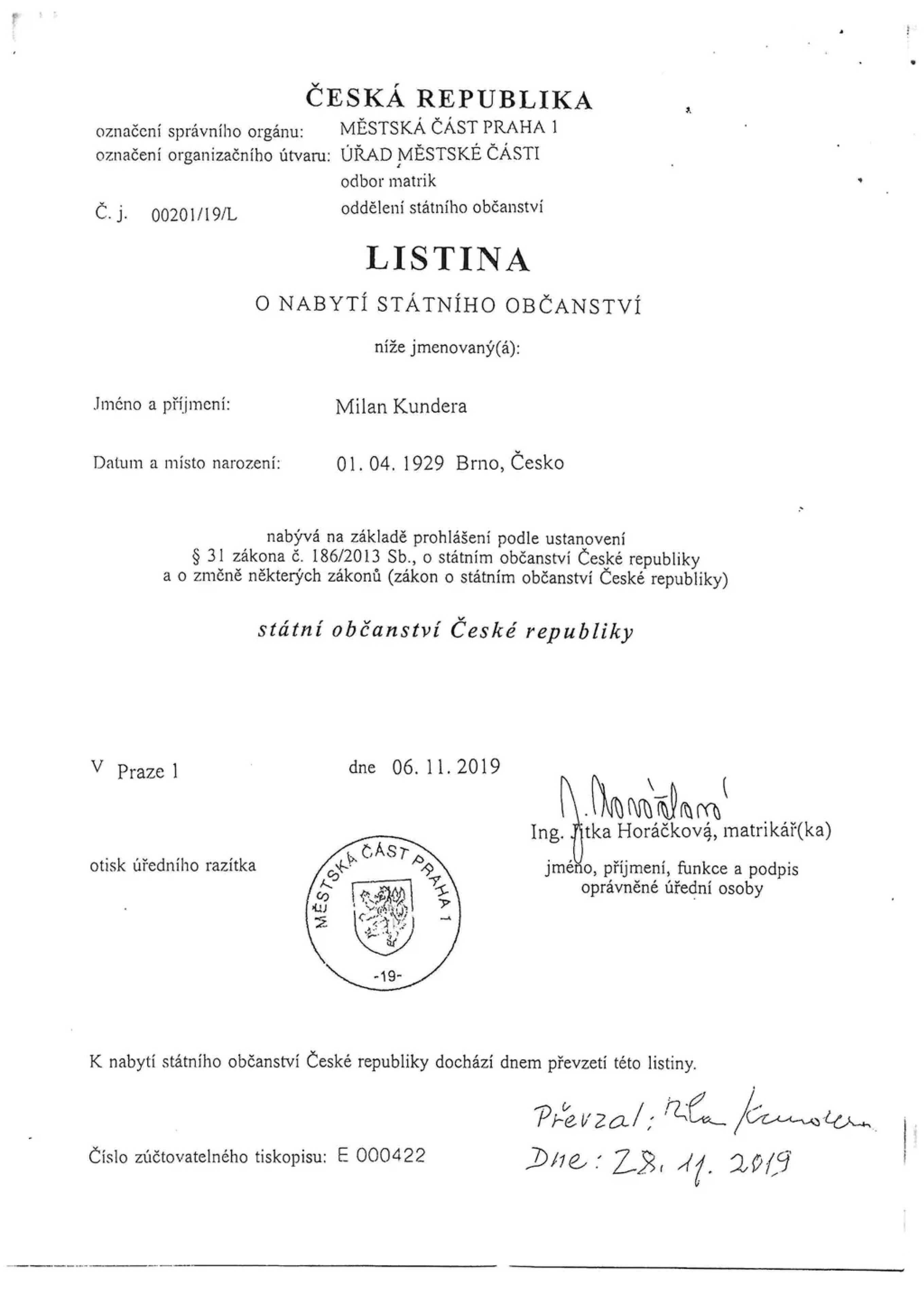

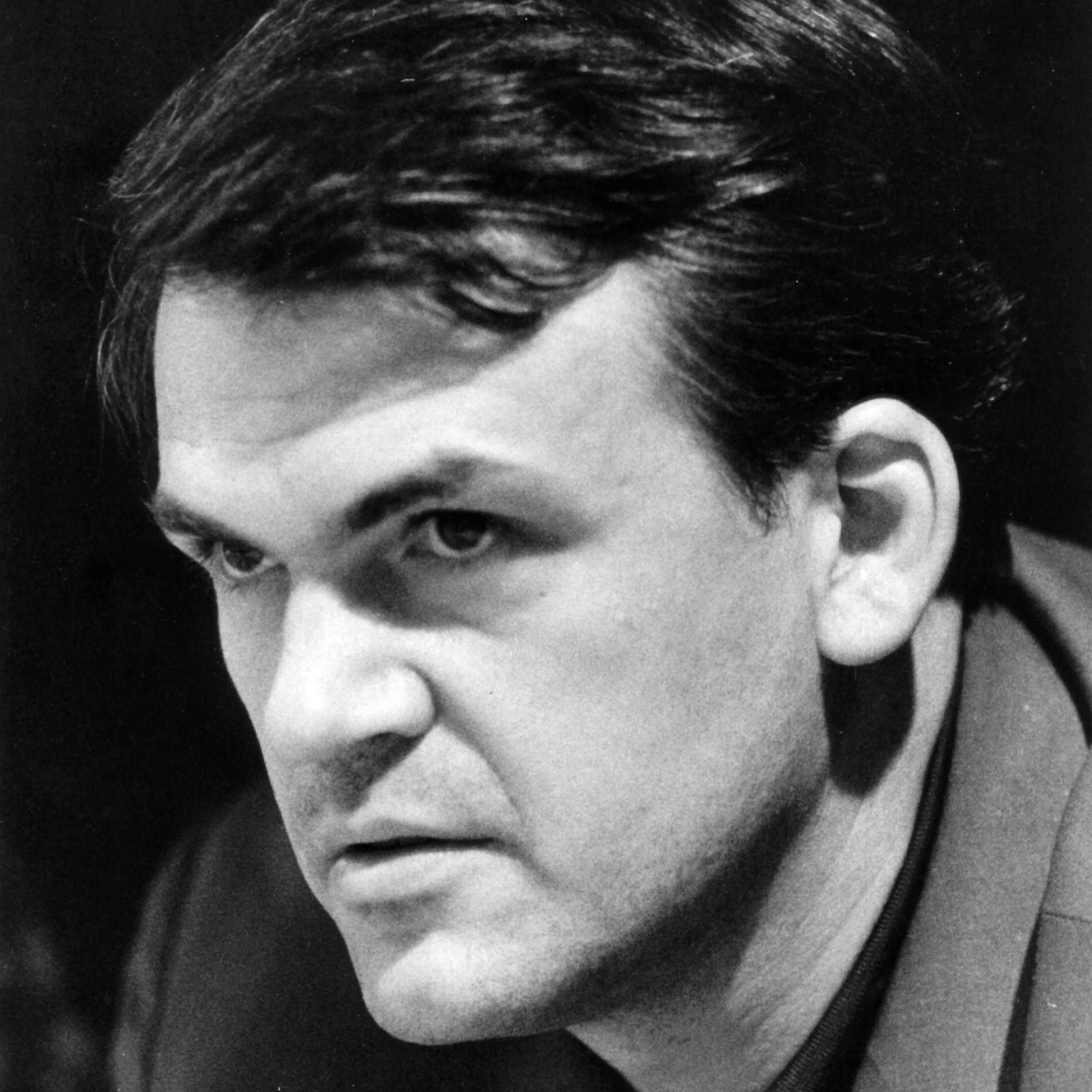

- Chemin, Ariane 2019. ‘L’écrivain, aujourd’hui âgé de 90 ans, avait été naturalisé français après avoir été déchu de sa nationalité’, La République tchèque a rendu à Milan Kundera sa nationalité, quarante ans après, 03 décembre 2019.

- Chemla, David. ‘Ensemble des écrits à redispatcher’.

- ———. 2011. ‘Gardons-nous de nous laisser entraîner dans le refus de l’autre, Entretien avec Michel Serfaty.’ in David Chemla (ed.), JCall: les raisons d’un appel ( Liana Levi Paris).

- ———. 2013. “Présentation du programme.” In JCall trip to Israel and Palestinian Territories. Tel Aviv: JCall.

- Cherruau, Pierre. 2001. “Luc Lagouche: Dans le club qu’il a créé à Kano, au Nigéria, il s’obstine à faire jouer ensemble musulmans et chrétiens, alors que règne la charia.” In Télérama, 40-41.

- Cheshire, J. 1991. English Around the World: Sociolinguistic Perspectives (Cambridge University Press,: Cambridge,).

- Cheshire, Jenny. 2011. “Adolescents as linguistic innovators: dialect contact and language contact in present-day London.” In Langues en contact: le français à travers le monde. Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg.

- Chevallier, Anne-Claire. 2000. “Francophones.” In Télérama, 6.

- Chevreul, Michel-Eugène. 1839. De la loi du contraste simultané des couleurs.

- Chiswick, B. (ed.)^(eds.). 1992. Immigration, Language and Ethnicity (The AEI Press: Washington D.C.).

- Chomsky, Noam. 1977. Dialogue avec Mitsou Ronat (Flamarion: Paris).

- ———. 2000. ‘Al-Aqsa Intifada’, Mid-East Realies. http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/51a/092.html.

- Chomsky, Noam, and Morris Halle. 1968. The Sound Pattern of English (Harper and Row: New York).

- Chrétien, Jean. 1997. “APEC CEO Summit Opening Ceremony Keynote Address, Vancouver, British Columbia.” In.: e-mail.

- ———. 1997. “Prime Minister to Host 5th APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting in Ottawa, Ontario.” In.: e-mail.

- Chumbow, B. S. . 2010. “Towards a legal framework for language charters in Africa.” In “Language, Law and the Multilingual State” 12th International Conference of the International Academy of Linguistic Law Bloemfontein, Free State University.

- Churchill, S. 1986. The Education of Linguistic and Cultural Minorities in OECD Countries (Multilingual Matters: Philadelphia).

- Cinquin, Chantal 1989. ‘President Mitterand Also Watches Dallas: American Mass Media and French National Policy.’ in Roger Rollin (ed.), The Americanization of the Global Village: Essays in Comparative popular Culture (Bowling Green State University Popular Press: Bowling Green).

- Clarini, Julie. 2014. ‘Zeev Sternhell, une passion française’, Le Monde, 24 mai 2014.

- Clark, Gordon L. , Dean Forbes, and Roderic Francis (ed.)^(eds.). 1993. Multiculturalism, Difference and Postmodernism (Longman Cheshire: Melbourne).

- Clarke, T , and B. J. Galligan. 1995. ”Aboriginal Native’ and the Institutional Construction of the Australian Citizen 1901-48.’, Australian Historical Studies, 26: 523-43.

- Clarkson, Adrienne. 1999. ‘Exerpts from her adress on Thursday Oct.7, 1999: to be complex does not mean to be fragmented” – At her installation yesterday, Canada’s new Governor-General spoke of “the paradox and the genius of our Canadian civilization”‘, The Globe and Mail, Friday, Oct. 8, 1999, pp. A11.

- ———. 1999. ‘Governor’s General Address’, The Globe and Mail, Friday, October 8, 1999, pp. A11.

- Claude, Patrice. 2000. ‘Et si un ou une papiste montait bientôt sur le trône d’Angleterre’, Le Monde, Mercredi 1er Novembre 2000, pp. 1.

- Clément, Catherine. 2006. Qu’est-ce qu’un peuple premier ? (Ed. du Panama: Paris).

- Cloonan, J.D., and J.M. Strine. 1991. ‘Federalism and the development of language policy: preliminary investigations’, Language Problems and Language Planning: 268-81.

- Cloud, N., F Genesee, and E. Hamayan. 2000. Dual Language Instruction: A handbook of enriched education (Heinle & Heinle: Boston).

- Clyne, Michael, G. 1992. Community Languages in Australia (Oxford University Press: Oxford).

- Clyne, M.G. 1985. Multilingual Australia: Resources, Needs, Policies. (Monash University Press: Burnley, VIC).

- Clyne, Michael G.., in , vol. , No. , april 1997. 1997. ‘Language policy in Australia: achievements, disappointments, prospects’, Journal of Intercultural Studies, 18: 63-71.

- Cobarrubias, J., and Fishman J. (ed.)^(eds.). 1983. Progress in Language Planning, International Perspectives (Mouton: Berlin).

- Cohen, Eliaz. 2013. “Un poète au Goush Etsion.” In JCall trip to Israel and Palestinian Territories, edited by David Chemla. Tel Aviv: JCall.

- Cole, Michael, and Jerome S Bruner. 1972. ‘Cultural differences and inferences about psychological processes’, American

- Psychologist: 867-76.

- Colombo, Jean Robert (ed.)^(eds.). 1991. The Dictionary of Canadian Quotations (René Lévesque) (Stoddart: Toronto).

- Combes, Mary Carol. 1992. ‘English Plus: Responding to English Only.’ in James Crawford (ed.), Language Loyalties: A source-book on the Official English ControversyCrawford, James (The University of Chicago Press: Chicago).

- Combesque, Agnès. 1999. ‘Comme des papillons vers la lumière’, Le Monde Diplomatique: 16 et 17.

- Commissaire, aux Langues Officielles. 1990. “Rapport Annuel 1989.” In. Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles.

- ———. 1991. “Rapport Annuel 1990.” In. Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles.

- ———. 1992. “Rapport Annuel 1991.” In. Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles.

- ———. 1993. “Rapport Annuel 1992.” In. Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles.

- ———. 1994. “Rapport Annuel 1993.” In. Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles.

- ———. 1995. “Rapport Annuel 1994.” In. Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles.

- ———. 1996. “Rapport Annuel 1995.” In. Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles.

- ———. 1997. “Rapport Annuel 1996.” In. Ottawa: Commissariat aux Langues Officielles.

- Commission. 1991. “Human Rights and Equal Oppportunity Commission.” In.

- Commission, Aboriginal Lands Rights. 1973. “First Report.” In. Canberra: Australian Parliament.

- ———. 1974. “First Report.” In. Canberra: Australian Parliament.

- Commonwealth. 1984. “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984.” In. Canberra: Commonwealth.

- Conley, John M. , and William O’Barr. 1998. Just Words: Law, Language and Power (University of Chicago Press: Chicago).

- Conseil, de l’Europe. 1991. “Europe 1990-2000: Multiculture dans la Cité, l’Intégration des immigrés.” In Conférence permanente des pouvoirs locaux et régionaux de l’Europe. Francfort-sur-le-Main: Les Editions du Conseil de l’Europe.

- ———. 2001. “Cadre européen commun de référence pour les langues: apprendre, enseigner, évaluer.” In.: Didier.

- Cook, Ramsay. 1986. Canada, Québec and the uses of Nationalism (McClelland & Stewart: Toronto).

- Cooper, R.L. 1989. Language Planning and Social Change ( Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).

- Coronel Molina, Seraphin. 2012. ” Indigenous Languages as Cosmopolitan and Global Languages: The Latin American Case.” In Languages in the City. Berlin.

- Correa da Costa, Sergio. 1999. Mots sans Frontières (Editions du Rocher: Paris).

- Corrigan, Tim. 1991. A Cinema Without Walls: Movies and Culture After Vietnam (Routledge: London).

- Corson, David. 1997. ‘Social Justice in the Work of ESL Teachers.’ in William Eggington and Helen Wren (eds.), Language Policy:

- Dominant English, pluralist challenges (John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam/Philadelphia).

- Corson, D, and S Lemay. 1996. Social Justice and Language Policy in Education: The Canadian Research (OISE Press: Toronto).

- Cortanze (de), Gérard. 2002. Assam (Albin Michel: Paris).

- Coulmas, Florian. 1991. ‘The Language Trade in the Asian Pacific’, Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 2: 1-27.

- ———. 1992. Language and Economy (Basil Blackwell: Oxford).

- Courtney, John C. 1996. Do Conventions Matter? : Choosing National Party Leaders in Canada (McGill Queens University Press).

- Couzens, Vicki, and Christina Eira. 2014. ‘Meeting point: Parameters for the study of revival languages. .’ in Peter K. Austin and Julia Sallabank (eds.), Endangered languages: Beliefs and ideologies in language documentation and revitalisation (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK).

- Craven, I. (ed.)^(eds.). 1994. Australian Popular Culture (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).

- Crawford, James. 1978. ‘English and Colonialism in Puerto Rico.’ in James Crawford (ed.), Language Policy Taskforce on Language Loyalties: A source-book on the Official English Controversy (The University of Chicago Press: Chicago).

- ——— (ed.)^(eds.). 1988. The Rights of Peoples (Clarendon Press: Oxford).

- ———. 1989. Bilingual Education: History, Politics, Theory and Practice (Crane Publishing: Trenton, New Jersey).

- ———. 1992. Hold your Tongue (Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Reading, MA).

- ———. 1992. Language Loyalties: A Sourcebook on the Official English Controversy (University of Chicago Press: Chicago).

- Creel, George. 1947. Rebel at Large: Recollections of Fifty Crowded Years (G.P. Putnam’s Sons: New York).

- Creissen, Thomas. 2020. “Art des premiers chrétiens et art byzantin.” In, edited by Cours d’initiation à l’histoire générale de l’art. Paris: Le Louvre.

- Crépeau, François, Stéphanie Fournier, and Lison Néel (ed.)^(eds.). 19991. Séminaire International de Montréal sur l’Education Interculturelle et Multiculturelle (Société Québécoise de Droit International: Montréal).

- Crépon, Marc. 2000. Le Malin Génie des langues (J. Vrin: Paris).

- Crowley, Terry. 1998. An Introduction to Historical Linguistics (Oxford University Press: Oxford).

- Crystal, David. 1995. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of English Language (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).

- ———. 1997. English as a Global Language (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).

- Cubertafond, Bernard. 1995. L’Algérie contemporaine (PUF: Paris).

- Culhane, J.G. 1992. ‘Reinvigorating Educational Malpractice Claims: A Representational Focus”‘, Washington Law Review, 2: 349-414.

- Cumming, Alister. 1997. ‘English Language-in-Education Policies in Canada.’ in William Eggington and Helen Wren (eds.), Language Policy: Dominant English, pluralist challenges (John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam/Philadelphia).

- Cummins, J. (ed.)^(eds.). 1984. Heritage languages in Canada: Research Perspectives (OISE Press: Toronto).

- ———. 1989. ‘Heritage language teaching and the ESL student: fact and friction.’ in J. Esling (ed.), Multicultural Education and Policies: ESL in the 1990s (OISE Press: Toronto).

- Cunningham, S. 1992. Framing Culture: Criticism and Policy in Australia (Allen & Unwin: Sydney).

- Cusin, Philippe. 1999. ‘Abd el-Krim, le Mythe du Rebelle’, Le Figaro Littéraire, 12 aout, pp. 3 (17).

PART 2: Detailed list

Cadart, Jacques (1990), Institutions politiques et droit constitutionnel (Paris: Economica).

p. 607 : Cité par Pierré-Caps, Stéphane (1996), ‘Deuxième Partie: Le Droit des Minorités’, in Norbert Rouland (ed.), Droit des Minorités et des Peuples Autochtones (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France), p. 300: (l’auteur) qualifie la Suisse de “démocratie des minorités, démocratie équilibrée par les minorités”

609: “chaque citoyen est membre de plusieurs groupes presque tous minoritaires mais il n’est jamais majoritaire dans plus d’un groupe et en ce cas seulement dans un groupe religieux ou linguistique”

Cain, Bruce. (1992.), ‘Voting rights and democratic theory: toward a colour-blind society’, in Grofman B. and Davidson C. (eds.), Controversies in minority voting: the voting rights act in perspective (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution).

Cairns, Alan. (1991), ‘Constitutional change and the three equalities’, in Ronald Watts and Douglas Brown (eds.), Options for a new Canada. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

___(1995), ‘Aboriginal Canadians, citizenship and constitution’, Reconfigurations: Canadian citizenship and constitutional change (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart).

Cajete, G., K. Nuuhiwa, et al. (2011). Ancestral knowledge of Sacred places. World Conference on the Education of the Indigenous People (WIPCE 2011). Cusco, Peru.

Calderon, Laurence and Gilli, Charles (2015), ‘Silence! On tourne: l’interactivité au service de l’analyse cinématographique’, paper given at Journée d’étude internationale EDUCATION AU CINEMA: histoire, institutions et supports didactiques, Cinémathèque de Lausanne, 31 janvier 2015.

Présentation d’un didacticiel interactif (DVD-Rom) axé sur le visuel . Extraits de films par notions. Intention de prendre la plus grande variété d’extrait possible pour convier l’élève à un petit parcours culturel de l’histoire du cinéma. Brièveté qui coupe la dimension de rêve cinématographique pour en faire un objet d’étude et cela peut susciter la curiosité. Proposer un seul support pour beaucoup d’extrait, très interactif sans l’obstacle de la linéarité d’un document. Ne pas se substituer à l’enseignant mais lui servir de support. Production de 3 DVD rom sur

1) le montage

2) achevé en 2008

3) l’image au cinéma, réalisé en 2008-10

Diffusé dans les CEDOC Romands

Droit de citation art. 25 fédéral sur droit de citation (non commercial et aspect pédagogique). Utilisable aussi sur moodle et accessible dans le secondaire II. aspect du cadrage et du point de vue.

Calhoun, Craig . 2005. Cosmopolitanism and Belonging. Paper read at 37th International Institute of Sociology Conference: Migration and Citizenship, at Stockholm, Norra Latin, Aula 3d Floor.

other Presenters: Morawska, Ewa, University of Essex: Immigrants and Citizenship: An Ethnographic Assessment Turner, Brian National University of Singapore, Global Religion, Diaspora and the Future of Citizenship Question in the real world affairs and categories of sociology, to belong or not to belong, cf. U. Beck. Cosmopolitan question. Some people can ask the question more freely. Cf. Analysis of Global Inequality Cosmopolitan Elite of frequent international travellers. Inhabitation of the world seen as superficially cosmopolitan. Post 9/11 created a divide between Euro-US and the rest of the world. “Global Order Control Regime”. Belief that nation matters less. Sense of connection to the World as a whole. Cosmopolitan Elites are hardly free. Secularism rule finds religion odds, virtuous deracination. Idea of citizenship and rights, political liberal theory. Earlier liberalism focused on nations, tacitely assuming that this was the ideal account of where people came from. Prioritization of individual values. Most inequalities are inter-societal. Cosmopolitan theorists take scale of humanity. Multiculturalism falls under suspicion. Morally questional move to a morally irrelevant sense of belonging. US Melting Pot: in the US, all is melted into one culture. In the 70s, rise of the unmeltable ethnic groups. Deep anxiety that hispanics don’t want to integrate (S. Huntington). In fact they can’t. Mixed race identity issue. Illusion that intermarriage will erase racism. Before Zangwill, there had been other accounts of the melting pot. Cf. Zionist theory of Zangwill: “a land without people for a people without a land” (abt Israel). Neglects to address issues about why some refuse this model. Hierarchy of belonging for cosmopolitans. cf. example of European constitution: pan european public sphere. Fear created strange alliances. Who wins and loses is still an open question. “Unification favours the dominants”, Bourdieu about Algeria.

Calvet, Louis-Jean et Alain. Le Poids des langues. Université d’Aix-en-Provence http://podcast.univ-provence.fr/~colloques/Podcast/Drop%20Box/calvets.pdf

- 1993. L’Europe et ses Langues. Paris: Plon.

- 1996. Les Politiques Linguistiques. Vol. 3075. Paris: PUF Que-Sais-Je?

- 2004. Essais de linguistique: la langue est-elle une invention des linguistes? Paris: Plon.

12: Trop longtemps en effet a régéné ce que j’appelerais volontiers le syndrome de Jéricho: l’idée qu’en tournant autour de la citadelle générativiste ou fonctionnaliste, en claironnant que la langue est un fait social, les (socio)linguistes allaient faire que les murailles de la linguistique mécaniste finissent par s’écrouler

cf. sur langues juives les pp.91 et ss. et chapitre 9 sur le plurilinguisme alexandrin 239: (…)Barthes concluait son texte par une phrase qui figure en exergue de mon Linguistique et Colonialisme: “Voler son langage à un homme au nom même du langage, tous les meurtres égaux commencent par là”

- 1974. Linguistique et Colonialisme: Petit Traité de Glottophagie. Paris: Bibliothèque Scientifique Payot.

- 1981. Les Langues Véhiculaires. Paris: PUF Que-Sais-Je?

Camus, Renaud (2012), ‘Même pas contre: Le mariage gay, c’est trop la honte pour l’homosexualité’, Causeur, (53).

Un article contre le « mariage gay », Patronne ? Mais c’est que je n’ai pas que ça à faire, moi ! Je travaille, j’ai une famille de chiens à nourrir, un branlant manoir à soutenir, un parti politique à conduire au pouvoir, sept ou huit livres à mener de front pour essayer de ne pas trop mourir de faim. Vous n’auriez rien de plus sérieux, comme sujet à me proposer ? Dois-je vous rappeler que la France est en train de changer de peuple, que l’Iran va avoir la bombe, que la démographie de notre pays connaît la croissance la plus alarmante d’Europe, que 60 000 hectares sont artificialisés tous les ans, que si ça continue comme ça, la banquise va bientôt croiser au large de la Casamance ?

Parlons-en, de la banquise. Moi qui suis phoque autant qu’on peut l’être, même si j’ai fait valoir mes droits à la retraite, et ancien combattant du front achrien, gay d’honneur malgré les soucis, votre histoire de « mariage gay », là, je ne veux même pas être contre, tellement je trouve ça ridicule. Qu’ils se marient s’ils le veulent, je ferai semblant de ne pas les connaître. D’ailleurs, je n’en connais déjà pas, de candidats à cette farce. Non, vraiment, c’est trop la honte pour l’homosexualité, cette histoire, et surtout pour l’amour des hommes. Abaisser « tout ce triomphe inouï », comme on dit dans Parallèlement1, à une imitation kitsch de l’hétérosexualité, ramasser ses restes, en somme, au moment où elle les oublie dans son assiette, ah non ! Entre nous, c’est encore un coup de l’égalité qui, décidément, n’en ratera pas une. C’est comme si les géants voulaient être jockeys, au prétexte qu’y a pas de raison. Vous voyez Verlaine et Rimbaud devant M. Raoult, vous ? Whitman convolant en juste noces avec un de ses camerados ? Rien que d’y penser, on tournerait straight, sans vouloir vous désobliger.

Ce n’est pas à vous que je devrais dire ça, Patronne, mais non, c’est vraiment trop débandant, comme idée. Vous en avez déjà vu, des mariages gays ? On se croirait chaque fois dans un gâteau Leader Price, sous sa coquille en plastique. Et plus ça a coûté, plus ça fait travelo au carré, Michou délocalisé à Cannes. Moi je crois que l’esthétique dit la vérité des choses : wysiwyg – vous voyez l’enveloppe, vous savez à peu près ce que dit la lettre.

J’avoue qu’entre les chars de la Gay Parade et les dessins de Jean Cocteau, j’ai toujours eu un problème avec le folklore pédérastique.Comme les garçons, pour moi, c’est l’objet du désir, et que je ne sais rien de moins sexy que tout ça, de mieux coupe-la-chique et petit-bourgeois, je ne me sens pas concerné. L’adoption, bon, là, je ne dis pas. L’homosexualité, y compris la plus chaste et collet monté, a les meilleures références en matière de pédagogie, depuis vingt-cinq siècles et plus. Je me demande même si ce n’est pas elle qui l’a inventée. Hélas c’est l’adoption en général, pas spécialement l’homosexuelle, qui me semble à remettre en cause. Trouver des parents aux enfants, très bien. Mais des enfants aux parents…

Parallèlement est un recueil de poèmes de Verlaine publié en 1889 (NDLR). ↩

Cet article a été publié dans le Magazine Causeur n° 53 – Novembre 2012

Canada. 1990. Loi sur le multiculturalisme canadien, Guide à l’intention des Canadiens. Ottawa.

Article 3.(1) paragraphe a. “La politique du gouvernement fédéral en matière de multiculturalisme consiste à reconnaître que le multiculturalisme reflète la diversité culturelle et raciale de la société canadienne et reconnaît la libert éde tous ses membres de maintenir, de favoriser et de partager leur patrimoine culturel, ainsi qu’à sensibiliser la population à ce fait” (p.13)

- Patrimoine. 1999. 10ème Rapport annuel sur l’application de la Loi sur le multiculturalisme canadien 1997-1998. Ottawa: Ministère du Patrimoine canadien.

Avant propos (de Jean Chrétien): Le Canada est reconnu pour sa richesse culturelle, et le modèle qu’il propose est devenu un exemple pour le monde entier. (…)

L’évolution des données démographiques et de la société canadienne confirme l’importance du multiculturalisme pour l’avenir du Canada, voire du monde entier.

message de (Hedy Fry), secrétaire d’état (multiculturalisme): (…)La politique du multiculturalisme a évoluté avec le temps. D’abord axée sur des groupes particuliers de la société, elle est devenue un moyen pour tous les Canadiens (…) de concrétiser les idéaux au coeur même de notre démocratie.(…) Par exemple, la Campagne du 21 mars de lutte contre l’élimination de la discrimination raciale est devenue l’élément le plus populaire et le plus visible des efforts que nous déployons afin d’éliminer le racisme au Canada.

——–(2013), ‘BACKGROUNDER: Aboriginal Offenders – A Critical Situation’.

quoted by Jamieson, Rebecca (2017), ‘A celebration of Indigenous Resilience’, paper given at WIPCE 2017, Toronto, 24-28 July 2017.

Outcome Gaps: Aboriginal vs. Non-Aboriginal Offenders

Aboriginal offenders lag significantly behind their non-Aboriginal counterparts on nearly every indicator of correctional performance and outcome. These men and women are:Routinely classified as higher risk and higher need in categories such as employment, community reintegration and family supports;

Released later in their sentence (lower parole grant rates), most leave prison at Statutory Release or Warrant Expiry dates;

Over-represented in segregation and maximum security populations;

Disproportionately involved in use of force interventions and incidents of prison self-injury; and

More likely to return to prison on revocation of parole, often for administrative reasons, not criminal violations.

High and Growing Incarceration Rates for Aboriginal Peoples

While Aboriginal people make up about 4% of the Canadian population, as of February 2013, 23.2% of the federal inmate population is Aboriginal (First Nation, Métis or Inuit). There are approximately 3,400 Aboriginal offenders in federal penitentiaries, approximately 71% are First Nation, 24% Métis and 5% Inuit.In 2010-11, Canada’s overall incarceration rate was 140 per 100,000 adults. The incarceration rate for Aboriginal adults in Canada is estimated to be 10 times higher than the incarceration rate of non-Aboriginal adults.

The over-representation of Aboriginal people in Canada’s correctional system continued to grow in the last decade. Since 2000-01, the federal Aboriginal inmate population has increased by 56.2%. Their overall representation rate in the inmate population has increased from 17.0% in 2000-01 to 23.2% today.

Since 2005-06, there has been a 43.5% increase in the federal Aboriginal inmate population, compared to a 9.6% increase in non-Aboriginal inmates.

Aboriginal Women: Aboriginal women are even more overrepresented than Aboriginal men in the federal correctional system, representing 33.6% of all federally sentenced women in Canada. According to Statistics Canada, “the disproportionate number of Aboriginal people in custody (is) consistent across all provinces and territories and particularly true among female offenders. In 2010/2011, 41% of females (and 25% of males) in sentenced custody (provincially, territorially and federally) were Aboriginal.” (Juristat, October 2012)

Aboriginal Youth: Aboriginal offenders tend to be younger than their counterparts. In 2013, 21.3% of all federally incarcerated Aboriginal offenders were 25 years of age or younger as compared to 13.6% of non-Aboriginals. The Aboriginal population in Canada is young. According to the 2006 Census data, nearly one-third (32%) of the 698,025 people who identified themselves as North American Indians (status and non-status Indians) were aged 0 – 14. Population projections released by Statistics Canada in 2005 show that Aboriginal people could account for a growing share of the young adult population over the next decade. By 2017, Aboriginal people aged 20 to 29 could make up 30% of that age cohort in Saskatchewan; 24% in Manitoba; 40% in the Yukon Territory; and 58% in the NWT.

Regional Aboriginal Offender Rates on the Rise

In the period between March 2010 and January 2013, the Prairies Region of the Correctional Service of Canada (primarily the provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta) accounted for 39.1% of all new federal inmate growth. Most of this growth was led by Aboriginal offenders, who now comprise 46.4% of the Prairie Region inmate population. Last month:At Stony Mountain Institution in Manitoba, 389 out of 596 inmates – 65.3% of the population – were Aboriginal;

At Saskatchewan Penitentiary, 63.9% of the population was Aboriginal;

At the Regional Psychiatric Centre in Saskatoon, 55.7% of the count was Aboriginal; and

At Edmonton Institution for Women, 56.0% of the population was Aboriginal.

So far this year, CSC’s Prairie Region leads the country in double bunking, lockdowns, self-harm incidents, inmate homicides and assaults.Factors Impacting Over-representation of Aboriginal People in Corrections

The high rate of incarceration for Aboriginal peoples has been linked to systemic discrimination and attitudes based on racial or cultural prejudice, as well as economic and social disadvantage, substance abuse and intergenerational loss, violence and trauma.These well-documented social, economic and historical factors have been recognized by the Supreme Court of Canada, originally in R. v. Gladue (1999) and reaffirmed in R. v. Ipeelee (2012): “To be clear, courts must take judicial notice of such matters as the history of colonialism, displacement, and residential schools and how that history continues to translate into lower educational attainment, lower incomes, higher unemployment, higher rates of substance abuse and suicide, and of course higher levels of incarceration for Aboriginal peoples.” (Justice LeBel for the majority in R. v. Ipeelee, 2012)

Correctional decision-makers must take into account Aboriginal social history considerations when liberty interests of an Aboriginal offender are at stake (e.g. security classification, penitentiary placement, community release, disciplinary decisions). These Gladue factors include:

Effects of the residential school system.

Experience in the child welfare or adoption system.

Effects of the dislocation and dispossession of Aboriginal peoples.

Family or community history of suicide, substance abuse and/or victimization.

Loss of, or struggle with, cultural/spiritual identity.

Level or lack of formal education.

Poverty and poor living conditions.

Exposure to/membership in, Aboriginal street gangs

Canovan, Margaret. 1996. Nationhood and Political Theory. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Capotorti, Francesco (1979), ‘Etude des droits des personnes appartenant aux minorités ethniques, religieuses et linguistiques.’ Centre pour les Droits de l’Homme (Genève: Sous-commission de la lutte contre les mesures discriminatoires et de la protection des minorités des Nations Unies ).

cité (entre autres) par Pierré-Caps, Stéphane (1996), ‘Deuxième Partie: Le Droit des Minorités’, in Norbert Rouland (ed.), Droit des Minorités et des Peuples Autochtones (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France), pp. 218-219

A la fois enquête exhaustive sur les situations minoritaires dans le monde, assortie d’une évocation des politiques gouvernementales à leur encontre, mais aussi oeuvre conceptuelle, cette étude possède, à ce dernier titre, le mérite de délivrer une définition éclairante de la notion deminorité entendue comme “un groupe numériquement inférieur au reste de la population d’un Etat, en position non domiante, dont les membres -ressortissants de l’Etat- possèdent du point de vue ethnique, religieux ou linguistique, des caractéristiques qui diffèrent de celles du reste dela population et manifestent, même de façon implicite, un sentiment de solidarité, à l’effet de préserver leur culture, leurs traditions, leur religion ou leur langue”

(…) il est permis de se demander si la définition du Pr. Capotorti n’a pas aujourd’hui acquis valeur coutumière, même si certains auteurs lui reprochent essentiellementd’exclure de son champ d’analyse les minorité nationales.

Egalement cité dans le même ouvrage par Norbert Rouland p. 415.

Carby V., Hazel. 1999. Cultures in Babylon. London and New York: Verso.

Caravedo, Rocío and Klee, Carol A. (2012), ‘Migración y contacto en Lima: el pretérito perfecto en las cláusulas narrativas’, Lengua y migración / Language and Migration, 4 (2).

Communicated by Maria Sancho, an SLonFB member, in November 2012. Other papers in this issue:

2. “Linguistic identity and the study of Emigrant Letters: Irish English in the making” – Carolina P. Amador-Moreno y Kevin McCafferty

3. “Reducción de /-s/ final de sílaba entre transmigrantes salvadoreños en el sur de Texas” – José Esteban Hernández y Rubén Armando Maldonado

4. “La migración sefardí en la Amazonia brasileña: lengua hakitía e identidad” – Carlos Cernadas Carrera

5. Reseña: Francisco Lorenzo, Fernando Trujillo y José Manuel Vez, Educación bilingüe. Integración de contenidos y segundas lenguas – Olga Cruz Moya

Carens, Joseph (1995) ‘Citizenship and aboriginal self-government’, (Ottawa: Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples).

___(1987.), ‘Aliens and citizens: the case for open borders’, Review of Politics, 3 ( 49).

Carey, Jonathan. 2018. ‘The Africans Who Called Tudor England Home: Hundreds of Africans lived freely during the reign of Henrys VII and VIII.’, Atlas Obscura, Accessed June 5, 2020.

At the College of Arms in London on a 60-foot-long vellum manuscript sits an image of a man atop a horse, with a trumpet in hand and a turban around his head. This is John Blanke, a black African trumpeter who lived under the Tudors. The manuscript was originally used to announce the Westminster Tournament in celebration of the 1511 birth of Henry, Duke of Cornwall, Henry VIII’s son. Blanke was hired for the court by Henry VII. The job came with high wages, room and board, clothing, and was considered the highest possible position a musician could obtain in Tudor England.

Blanke was no anomaly, but was one of hundreds of West and Northern Africans living freely and working in England during the Tudor dynasty. Many came via Portuguese trading vessels that had enslaved Africans onboard, others came with merchants or from captured Spanish vessels. However once in England, Africans worked and lived like other English citizens, were able to testify in court, and climbed the social hierarchy of their time. A few of their stories are now captured in the book, Black Tudors by author and historian Miranda Kaufmann.

cf. Jan Mostaert’s 16th-century painting Portrait of an African man.

Pulling from exchequer papers, parish records, letters, and petitions, Kaufmann pieces together the lives of 10 Africans living in Tudor England. She sets out to change the way we understand Tudor life, Medieval England, and dispel the notion that the first Africans arrived in England as slaves. “Once people learn of the presence of Africans in Tudor England, they often assume their experience was one of enslavement and racial discrimination,” Kaufmann writes in her opening introduction.The idea that Africans were mistreated by the English well before the Atlantic slave trade comes from a Queen Elizabeth I letter sent to the Privy Council in 1596, a sort of board of directors for England. In the letter Queen Elizabeth I largely blamed the African population for England’s ongoing social issues, writing that the country did not need “divers blackmoores brought into this realme.” This proclamation was sent to the mayors of England’s major cities. She later arranged for a merchant named Casper van Senden to deport Africans from England.

However, this edict wasn’t what it appeared. Kaufmann writes that van Senden originally approached the queen telling her that Africans were taking jobs away from English citizens, a problem that could be readily solved by paying him to deport them. “In the queen’s understanding, everyone she cared about would profit: there would be more work for good English folk who would then complain less to the queen, and a grateful merchant would make money from her kind deal. But like several other of Elizabeth’s schemes, they solved a problem that nobody really saw or worried about,” says Janice Liedl, Professor of History at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario.

There was one caveat in the proclamation: as Kaufmann notes, deportation was based on the consent of their masters, which in this case was likely in the context of an apprenticeship. In 1569 an English court ruled that “England has too pure an air for slaves to breathe in,” setting the first legal precedent barring slavery from England. This was so well known that according to Kaufmann the idea of England as a free land reached slaves working in Mexican silver mines. Juan Gelofe, a 40-year-old West African slave working in the mines around 1572 told an English sailor by the name of William Collins that England, “must be a good country as there are no slaves there.” The merchants thus refused to comply with the edict, unwilling to lose their African apprentices. This prompted van Senden to plead with the council to expand his authority over the situation. A second letter went out from the queen, but it too was largely unsuccessful and ignored.

While the African population in England would have been relatively small, possibly a little more than 300 individuals according to Kaufmann, they were respected members of Tudor society. In Black Tudors the importance of the church is discussed at great length. Through her research, Kaufmann uncovered evidence that Africans were married and baptized by the Church of England. More than 60 Africans were baptized in England between 1500 and 1640, along with hundreds of burials. “The church was the central social and cultural institution. Your membership in the church helped cement you as a legal person—if you became poor, sick or were injured, your parish had an obligation to take care of you,” says Liedl. The church gained further importance after King Henry VIII’s reformation where you could be tried as a heretic for not attending church, according to Liedl.

cf. A tapestry showing the meeting of Kings Henry VIII and François I, c. 1520

As Black Tudors details, Africans weren’t just members of society but were present during some of the major events of the Tudor era. Jacques Francis, a salvage diver from Guinea in West Africa, worked the wreck of the Mary Rose and Diego the circumnavigator explored the globe with Francis Drake. The aforementioned John Blanke would have certainly enjoyed some celebrity during his time due to his position in the royal court. He even performed at Henry VIII’s coronation and married a London woman. So, what changed? What prompted England to become a key nation in promulgating the Atlantic slave trade?English expansion and colonization is often seen as the driving factor. In the 1640s the Dutch introduced sugar cane to the island of Barbados, showing Bajan planters how to cultivate the crop and providing them with African slaves as labor. Sugar dominated agriculture on the island, the English relied heavily on convict labor, but it was far scarcer than slaves. Taking their cues from the Dutch and to increase profits, the English began the triangular trade of African slaves to the Caribbean. But there was another factor, the transformation from the concept of slavery holding the generic meaning of another person owning another, to one defined by ethnic identities says Liedl. She explains that defining “white” and “black” in English literature comes from this decision toward the end of the Tudor period. The idea of racial superiority wasn’t a common theme in Tudor England. “As more black people were enslaved, Europeans began to write of black people as naturally slaves or as benefiting from slavery. These benefits included Christianity and civilization, both of which black Africans were assumed to lack,” says Leidl.

Carver, Craig. 1992. The Mayflower to the Model T: the development of American Eglish. In English in its Social Contexts: Essays in Historical Sociolinguistics,, edited by T. W. Machan and S. Ch.T. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Casey, John W. 1998. The Ebonics Controversy: Critical Perspectives on African-American Vernacular English. The Keiai Journal of International Studies 1 (1):179-214.

Envoyé par Bill Casey lui-meme. sur le genetical basis du premier draft.

180: Despite much impassioned -and often misinformed (see Rothstein, R. “The Myth of Public School Failure.” The American Prospect 13.Spring (1993).)- discussion in the United States over a decline in educational standards and the national debate over the methods and relevance of standardized testing procedures, averages for verbal scores on at least one major achievement test taken by many high school students have shown improvements in past years. In the period from 1980 to 1989 scores on the verbal section of the widely-administered SAT rose a modest 12 points from 387 to 399, leading observers to remark that despite overall deteriorating conditions in American schools, improvements in some areas are still evident.

181: (…) What strikes one most about the scores, however, is the large and persistent gap between white and black students in both verbal and math sections. In verbal skills alone this gap over the period in question measured close to 100 points (see table) And it remains so today with no apparent sign of narrowing. As a reflection of what is generally referred to in testing literature as “performance”, SAT scores are routinely used by universities in admission processes and, in this sense, are a measure of a student’s presumed marketability in an age when education has become more and more to assume the stark characteristics of basic skills traning to fill slots in a highly mobile and unpredictable labor pool.

In the Oakland, California Unified School District the average grade point average (GPA: scale of 4.0) in the 1995-96 school year for all students was 2.1. On this scale, sores for white and Asian-Americans were above 3.0, whereas African-American students found themselves at the bottom with an average of 1.80 -a startling figure considering 53% of the Oakland, California school district student population is black -one of the highest percentages in the United States.

(…) Although the history of black activism in the Oakland community dates from well before the 1960s, it was during that time community leaders took to the street to demand that he municipal goverment allocate tax funds in a more equal manner. It was in Oakland also that the Black Panther self-defense group first organized itself to confront police violence, to help provide poor African-Americans with better housing and jobs, and to teach inner-city children language skills and respect for black culture.

182: One might argue that the place of Oakland’s black community in the current debate over academic standards finds its roots, at least in parts, in differences betweenn Panghters on one hand and black cultural nationalists whose message to black children of the time was that, since Africa remained their ancestral home, all white cultural symbols should be rejected. Oakland’s Panther leadrs, on the other hand, argued for an approach built on radical democracy and less on purely cultural symbols as a means of instilling concepts of individual pride and self improvement. English, they insisted, was as much theirs as anyone’s (…).

In Contrast to cultural nationalists of the 1960s, Panthers appeared to see Englsih more as a political weapon with which they hoped to transform society. This dispute parallels a divide in social linguisitcs which often contraposes those who regard language as semehow peripheral to larger social and political questions with those who insist that language is a crucial factor in determining social discourse.(…) with this history of community activism as a background that the Oakland Unified School District unanimously passed a resolution on December 18, 1996, officially recognizing African American Vernacular English/Ebonics as -among other things – “genetically based”, a “legitimate language” and “not a dialect of English”. The board recommended that in light of the continual underperformance of young African-American in reading and wiring skills, the school district should be allowed to use funds from the U.S. Federal Bilingual Education Act to fund a program “featuring African Language Systgem principles to move students from the language pattens they bring to school to English proficiency”

183: After several days fo furious criticism from legislators, new wirters, political action groups, national politicians and a host of others, the board reconvened and amended the resolution removeing what were considered to be the most offending phrases.

184-85: Buat as has ofteh been the case, many of the strongest critics of the Ebonics resoultion were African-Americans. Some, like the Television personality Arsenio Hall (“it’s abusurd. Absurd. I think it creates awful self-esteem in black kids…”; cf. Olszewski, L. 1997. ‘Oakland Teachers Put Ebonics to the Real World Test”‘ The San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco.) and well known comedian Bill Cosby, (“legitimizing the street in the classroom is backwards”, Olszewski, L. 1997. ‘Oakland Teachers Put Ebonics to the Real World Test”‘ The San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco.) might possibly be dismissed as somehow lacking informed opinions. But of anumber of prominent black intellectuals involved in local and antional policy-making have also spoken out against the resolution. Ezola Foster, a veteran black educator in the Los Angeles Unified School District, joined (….) Senator Haynes as co-leader of a national campaing to oppose Ebonics. Respected black newspaper columnist William RASPBERRY ALSO APPEARED TO SEE LITTLE CONNECTION BETWEEN the social effects of language education policies and poor student academic performance when he remarked in the Washington Post (Raspberry, W. 1997. ‘Innovating Isn’t Educating’ The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.) that “the solution llie less in changing the way teachers teach than in the commitment of the rest of us -particularly the black middle class- to change the way these youngsters view their world”. Even Jesse Jackson, perhaps the most prominent liberal black leader in the U.S., initially called the resolution “an unacceptable surrender bordering on disgrace”

186: The genetic Basis of Language

The Board’s use of the term “genetically based” in referring to Ebonics was clearly the most controversial point in the entire December 18th resolution. It was quickly replaced in the amended version due to laud protest from around the country which accused the Oakland administrators of racial determinism, reverse discrimination, bigtry, and simple ignorance of human evolution and cognition.

Arthur Jensen [Jensen, A. 1969. ‘How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?’. Harvard Educational Review: 1-123.), basing his work on what was described as “verbal deprivatgion” theory, concluded that “racism, or the belief in the genetic inferiority of Negros, is a correct view in the light of the present evidence”. And genetics remains a factgor today in continued attempts by Amercian academics, such as Richard Herrnstein, Charles Murray, and others, to explain black academic inferiority.

187: Thus, if the English spoken by African-Americans were actually a kind of pidgin with a limited lexical range and no fixed grammar, it would only have persisted a generation or so before the process of creolization initiated by second-and third-generation speakers began to fill in the various linguistic gaps.

The only other conceivable intermpretation of the resoutions’s reference to genetics follows from the first condition: Ebon ics is a language variety spoken by a cognitively -subnormal group that because of a gentic predisposition can neither communicate effectively among themselves nor hope to speak any differently. In other workds, some AAVE speakers might like to learn SAE BUT are unable because of a genetic inability. Needless to say, this is clearly the veiw the board was contesting.

188: The members were clearly surprised atthe depth of reaction provoked by hteir resolution, and their subsequent willingness to amend the document would seem to imply that wording was not a vital issue. The board clearley used the term “genetically-based” without regard for the extreme interpretation it often carries and in the ensuing hail of criticism was unable to debate the essential triviality (in this context) of the phrase. In a later synopsis of the adopted policy the board writes “the term “genetically-based” is used, according to the standard dictionnary definition of “has origins in”. It is not used to refer to human biology”. This disclaimer stikes one as an attempt at backpedalling, hurriedly issued in response to accusation of racism, although in view of the above discussion it seems to be a meaningless concession.

To summarize, I believe we can view use of the term “genetically-based” in the Oakland resolution as both a political blunder, considering the eagerness withwhich so many groups used to condemn it, and as an unexceptional comment on the baiss of human language.

189: The point is that the Ebonics debate, occurring as it did in a highly conservative political atmosphere, with limited time constraints (the school board was holding its final session of the year) and within an ethnically divided community already sensitive to qustions of race and language, seemed almost destined to ignite despite this fairly common reference to a shared genticc trait that in other circumstances might have passed unnoticed.

190: In general, mutually comprehensible speakers are said to pssess the same language, although Chambers and Trudgill note a number of exceptions to this principle (…).

Dialects, on the other hand, are normally considered to exist within one language and to be mutually intelligible.

In a similar fashion to the prestige dialects in many othe rcountires, the SAE dialect in the United States has succeeded in capturaing a place as the national language (although this remains an extremely contentious issue today).

In light of these factors, it would seem reasonable then to regard SAE and AAVE equally as two deparate dialects of the english language. Although is very clearly the prestige form used for business and education, in purely linguistic terms (…) there is no basis for valuing one dialect over another. Even so, the word dialect obviously carries a number of negative connotations, and many linguists therefore prefer to use the term variety.Creoles (…) are fully formed natural languages evolving out of pigins, and this is the manner in which some historical linguist believe AAVE may have been formed.

Whether “creolization” is a viable origin for AAVE or not -and a number of researchers debate the point, Muhlhausler(Muhlhausler, P. 1986. Pidgin and Creole Linguistics. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.) notably, who contests the African “substratum” theory of a deep, core layer of bother grammar and lexicon underlying AAVE -it is important to keep in mind that te legitimacy of AAVE as a natural langauge does not depend in any way onthe resolution of this question.

191: (…) it has been suggested that AAVE lacks the appropriate grammatical means of expressing complex thought patterns and that its speakers are thereby somehow incapable of fully rational thought. Among other clains one commonly hears about AAVE are: that it cannot express tense and therefore its peakers wander in and out of temporal sppech at random; it is lazy speech which fails to show correct verb inflections and noun markers; its speakers enunciatiate poorly and do not pronounce certain SAE sounds properly; its speakers use verbal elements randomly, sometimes leaving them out altogether. Maany of these criticisms, although heard recently from opponenets of the Ebonics resoluiton are far from new. Some date back to the early days of African slavery in both the Americas and in West Africa – the principal “source” of slaves taken by Dutch, British and Portuguese traders.

Had 17th century businessmen exported their human commodity from a single port on the West African Coast, the likelihood of one or two African langauges persisting among a displaced populace would have been greatly enhanced. The policy among slavers, however, was to mix tribal and language groups in order to revent communication among prisoners and thereby to void revold. In his ook on the origins of American English, Dillard (Dillard, J.L. 1972. A History of American English. New York: Longman.) quotes an ealier historian who explains:

the means used by those who trade to Guinea, to keep the Negroes quiet, is to chose them from severall parts of ye Contry, of diffeeent Languages; so that they find they cannot act joyntly, when they are not in a Capacity of Consulting one an other, and this they can not doe, in soe far as they understand no one an other)

193: According to Loewen (Loewen, J.W. 1995. Lies My Teachers Told Me. New York: Routledge.), the first non-native settlers in the United states were actually black not white, since Spanish colonizers in the early 17th century had brought and later abandoned 100 slaves in what is now South Carolina.

In the sea islands of Georgia and South Carolina, Gullah is perhaps the best documented and notably the only African American creole whose West African originis remain uncontested.

The dramatic increase in slaves in Alabama, Mississipi, and Luisiana from 1820-40 thus began what has been called the “southernization” of Black English.

According to some researchers, large concentrations of slaves on a single plantation allowed for more intese linguistic interaction and some limited measure of family life, both of which led to a sustained community (Dillard, J.L. 1972. Black English: its History and Usage in the United States. New York: Random House.). But as mentioned earlier, plantations would not necessarily have been the boundaries of all social life. Under conditions such as these, the creole hypothesis is a distinct possibility, although in amny areas by the late 1800s it also appears that AAVE was undergoing a reverse process of decreolization inwhich features that were noticeably unlike the mainstream varietY (e.g. anterior verb markers such as de and blan) were being lost (Mufwene, S.S. 1997. ‘Gullah Development: Myth and Socio-historical Evidence’ in Berstein, C., Nunnally, T. and Rabino, R. (eds.) Language Variety in the South Revisited: The University of Alabama Press.)

Historical linguists mark the final stage in the evolution of AAVE from Emancipation throught the endo fo World War II. During this time a large number of newly liberated slaves began to congretate in isolated rural areas throughout the South (due largely to discriinatory policies established by the majority of white reisents, but in many cases through their own inititatives) to found all-black settlements.

195: The increasing monoculture of commercial television that began in the 1950s has had a leveling effect not only on AAVE but on many regional dialects.

The dying out or maintenance of minority language vaireties despite (or often in spite of) social or racial persecution is an historical phenomenon well documented by linguistst and ethnographers (cf. Edwards, J., Language 1985. Language, Society and Identity. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.).

cf. his description of AAVE, PP. 196-199

203: Linguistic usage, thus, cannot be analyzed apart from the society iwthin which it is used; it must be regarded as one element of a societal whole -historic, social, and eecononic. In describing the linguistic interactions between predominantly SAE-speaking teachers and AAVE-speaikng students in innercity schools, the question then becomes not so much what iis said but why it is communicated as it is. What social, economic, and historic influences have shaped the forms and social usage of both AAVE and SAE and the way they interact? How has SAE come to maintain its positin as the seemingly untentested national language to be used in exclusion of other varieties?Are there larger economic factors which make AAfrican-Aamericans and therefore the variety of English they speak less acceptable? To disregard such questions is to engage in a type of myopic elevation of common sense notions about language similar in some regards to childen’s assumptions that others should aslways want to play the game they are playing.

Fairclough (Fairclough, N. 1985. Language and Power. New York: Longman Publishing.) refers to this preempting of common sense assumption by one language vairety or discourse type and its resultant acceptance by a larger public as the “opacity of discourse”- an inability essentially to see through the historical imposition of one discourse upon others.The medium of instruction itself is seldom recognized as one language variety among others.

204: Of equal importance, however, is the way the opacity of discourse affects African-Americans as representatives of a large economic underclass. As a measure of the basic inequality of economic power in any society, the discourse of more powerful elements -corporate elites, gouvernment bureaucrats, media tycoons-will tend to replace other discrouse types through the process of normalilzati. Although a corporate perspective has come to imbue discourse in virtually every sector of society, it might be argued that ^due to AAVE’s relative isolation it has remianed less susceptbible of such influences. African-Amercan’s lower educational levels and hence ehtier restricted access to higher paying jobs (both of these, needless to say, affected by discriminatory attitudes within society) has ironically limited the influence corporate discours has had upon AAVE.

Despite resistance from African-Americans toward assimilation into white cullture, the attraction corporate culture holds for many youngh African Americans is powerful. Inevitably, this has transformed the way they speak.

205: CONCLUSION: As much as can be said about the importance of placing language in its social and historical context so that students may understand the role it plays in shaping their lives, one must guard against the reduction of social struggle to a simple discussion of language.

Rather than simply being places of inculcation in which the dominant patterns of society are rehearsed, schools can be and often are places that teach what might be called “liberation skills”. These can include lessons non only in critical language awareness (CLA)in which students learn to look at the reasons how and why different language vaireties are used, but also the practical skills necessray to change the conditions of oppressionin which students often find themselves.envoyé par Bill Casey lui-meme. sur le genetical basis du premier draft.180: Despite much impassioned -and often misinformed ( see Rothstein, R. “The Myth of Public School Failure.” The American Prospect 13.Spring (1993).)- discussion in the United States over a decline in educational standards and the national debate over the methods and relevance of standardized testing procedures, averages for verbal scores on at least one major achievement test taken by many high school students have shown improvements in past years. In the period from 1980 to 1989 scores on the verbal section of the widely-administered SAT rose a modest 12 points from 387 to 399, leading observers to remark that despite overall deteriorating conditions in American schools, improvements in some areas are still evident.181: (…) What strikes one most about the scores, however, is the large and persistent gap between white and black students in both verbal and math sections. In verbal skills alone this gap over the period in question measured close to 100 points (see table) And it remains so today with no apparent sign of narrowing. As a reflection of what is generally referred to in testing literature as “performance”, SAT scores are routinely used by universities in admission processes and, in this sense, are a measue of a student’s presumed marketability in an age when education has become more and more to assume the stark characteristics of basic skills traning to fill slots in a highly mobile and unpredictable labor pool.

In the Oakland, California Unified School District the average grade point average (GPA: scale of 4.0) in the 1995-96 school year for all students was 2.1. On this scale, sores for white and Asian-Americans were above 3.0, whereas African-American students found themselves at the bottom with an average of 1.80 -a startling figure considering 53% of the Oakland, California school district student population is black -one of the highest percentages in the United States.(…) Although the history of black activism in the Oakland community dates from well before the 1960s, it was during that time community leaders took to the street to demand that he municipal goverment allocate tax funds in a more equal manner. It was in Oakland also that the Black Panther self-defense group first organized itself to confront police violence, to help provide poor African-Americans with better housing and jobs, and to teach inner-city children language skills and respect for black culture.182: One might argue that the place of Oakland’s black community in the current debate over academic standards finds its roots, at least in parts, in differences betweenn Panghters on one hand and black cultural nationalists whose message to black children of the time was that, since Africa remained their ancestral home, all white cultural symbols should be rejected. Oakland’s Panther leadrs, on the other hand, argued for an approach built on radical democracy and less on purely cultural symbols as a means of instilling concepts of individual pride and self improvement. Engllish, they insisted, was as much theirs as anyone’s (…).In Contrast to cultural nationalists of the 1960s, Panthers appeared to see Englsih more as a political weapon with which they hoped to transform society. This dispute parallels a divide in social linguisitcs which often contraposes those who regard language as semehow peripheral to larger social and political questions with those who insist that language is a crucial factor in determining social discourse.(…) with this history of community activism as a background that the Oakland Unified School District unanimously passed a resolution on December 18, 1996, officially recognizing African American Vernacular English/Ebonics as -among other things – “genetically based”, a “legitimate language” and “not a dialect of English”. The board recommended that in light of the continual underperformance of young African-American in reading and wiring skills, the school district should be allowed to use funds from the U.S. Federal Bilingual Education Act to fund a program “featuring African Language Systgem principles to move students from the language pattens they bring to school to English proficiency”183: After several days fo furious criticism from legislators, new wirters, political action groups, national politicians and a host of others, the board reconvened and amended the resolution removeing what were considered to be the most offending phrases.184-85: Buat as has ofteh been the case, many of the strongest critics of the Ebonics resoultion were African-Americans. Some, like the Television personality Arsenio Hall (“it’s abusurd. Absurd. I think it creates awful self-esteem in black kids…”; cf. Olszewski, L. 1997. ‘Oakland Teachers Put Ebonics to the Real World Test”‘ The San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco.) and well known comedian Bill Cosby, (“legitimizing the street in the classroom is backwards”, Olszewski, L. 1997. ‘Oakland Teachers Put Ebonics to the Real World Test”‘ The San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco.) might possibly be dismissed as somehow lacking informed opinions. But of anumber of prominent black intellectuals involved in local and antional policy-making have also spoken out against the resolution. Ezola Foster, a veteran black educator in the Los Angeles Unified School District, joined (….) Senator Haynes as co-leader of a national campaing to oppose Ebonics. Respected black newspaper columnist William RASPBERRY ALSO APPEARED TO SEE LITTLE CONNECTION BETEWEEN the social effects of langauge education policies and poor student academic performance when he remarked in the Washington Post (Raspberry, W. 1997. ‘Innovating Isn’t Educating’ The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.) that “the solution llie less in changing the way teachers teach than in the commitment of the rest of us -particularly the black middle class- to change the way these youngsters view their world”. Even Jesse Jackson, perhaps the most prominent liberal black leader in the U.S., initially called the resolution “an unacceptable surrender bordering on disgrace”186: The genetic Basis of LanguageThe Board’s use of the term “genetically based” in referring to Ebonics was clearly the most controversial point in the entire December 18th resolution. It was quickly replaced in the amended version due to laud protest from around the country which accused the Oakland administrators of racial determinism, reverse discrimination, bigtry, and simple ignorance of human evolution and cognition.Arthur Jensen [Jensen, A. 1969. ‘How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?’. Harvard Educational Review: 1-123.), basing his work on what was described as “verbal deprivatgion” theory, concluded that “racism, or the belief in the genetic inferiority of Negros, is a correct view in the light of the present evidence”. And genetics remains a factgor today in continued attempts by Amercian academics, such as Richard Herrnstein, Charles Murray, and others, to explain black academic inferiority.187: Thus, if the English spoken by African-Americans were actually a kind of pidgin with a limited lexical range and no fixed grammar, it would only have persisted a generation or so before the process of creolization initiated by second-and third-generation speakers began to fill in the various linguistic gaps.The only other conceivable intermpretation of the resoutions’s reference to genetics follows from the first condition: Ebon ics is a language variety spoken by a cognitively -subnormal group that because of a gentic predisposition can neither communicate effectively among themselves nor hope to speak any differently. In other workds, some AAVE speakers might like to learn SAE BUT are unable because of a genetic inability. Needless to say, this is clearly the veiw the board was contesting.188: The members were clearly surprised atthe depth of reaction provoked by hteir resolution, and their subsequent willingness to amend the document would seem to imply that wording was not a vital issue. The board clearley used the term “genetically-based” without regard for the extreme interpretation it often carries and in the ensuing hail of criticism was unable to debate the essential triviality (in this context) of the phrase. In a later synopsis of the adopted policy the board writes “the term “genetically-based” is used, according to the standard dictionnary definition of “has origins in”. It is not used to refer to human biology”. This disclaimer stikes one as an attempt at backpedalling, hurriedly issued in response to accusioaation of racism, although in view of the above discussion it seems to be a meaningless concession.To summarize, I believe we can view use of the term “genetically-based” in the Oakland resolution as both a political blunder, considering the eagerness withwhich so many groups used to condemn it, and as an unexceptional comment on the baiss of human language.189: The point is that the Ebonics debate, occurring as it did in a highly conservative political atmosphere, with limited time constraints (the school board was holding its final session of the year) and within an ethnically divided community already sensitive to qustions of race and language, seemed almost destined to ignite despite this fairly common reference to a shared genticc trait that in other circumstances might have passed unnoticed.190: In general, mutually comprehensible speakers are said to pssess the same language, although Chambers and Trudgill note a number of exceptions to this principle (…).Dialects, on the other hand, are normally considered to exist within one language and to be mutually intelligible.In a similar fashion to the prestige dialects in many othe rcountires, the SAE dialect in the United States has succeeded in capturaing a place as the national language (although this remains an extremely contentious issue today).In light of these factors, it would seem reasonable then to regard SAE and AAVE equally as two deparate dialects of the english language. Although is very clearly the prestige form used for business and education, in purely linguistic terms (…) there is no basis for valuing one dialect over another. Even so, the word dialect obviously carries a number of negative connotations, and many linguists therefore prefer to use the term variety.Creoles (…) are fully formed natural languages evolving out of pigins, and this is the manner in which some historical linguist believe AAVE may have been formed.Whether “creolization” is a viable origin for AAVE or not -and a number of researchers debate the point, Muhlhausler(Muhlhausler, P. 1986. Pidgin and Creole Linguistics. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.) notably, who contests the African “substratum” theory of a deep, core layer of bother grammar and lexicon underlying AAVE -it is important to keep in mind that te legitimacy of AAVE as a natural langauge does not depend in any way onthe resolution of this question.191: (…) it has been suggested that AAVE lacks the appropriate grammatical means of expressing complex thought patterns and that its speakers are thereby somehow incapable of fully rational thought. Among other clains one commonly hears about AAVE are: that it cannot express tense and therefore its peakers wander in and out of temporal sppech at random; it is lazy speech which fails to show correct verb inflections and noun markers; its speakers enunciatiate poorly and do not pronounce certain SAE sounds properly; its speakers use verbal elements randomly, sometimes leaving them out altogether. Maany of these criticisms, although heard recently from opponenets of the Ebonics resoluiton are far from new. Some date back to the early days of African slavery in both the Americas and in West Africa – the principal “source” of slaves taken by Dutch, British and Portuguese traders.Had 17th century businessmen exported their human commodity from a single port on the West African Coast, the likelihood of one or two African langauges persisting among a displaced populace would have been greatly enhanced. The policy among slavers, however, was to mix tribal and language groups in order to revent communication among prisoners and thereby to void revold. In his book on the origins of American English, Dillard (Dillard, J.L. 1972. A History of American English. New York: Longman.) quotes an ealier historian who explains:the means used by those who trade to Guinea, to keep the Negroes quiet, is to chose them from severall parts of ye Contry, of diffeeent Languages; so that they find they cannot act joyntly, when they are not in a Capacity of Consulting one an other, and this they can not doe, in soe far as they understand no one an other)193: According to Loewen (Loewen, J.W. 1995. Lies My Teachers Told Me. New York: Routledge.), the first non-native settlers in the United states were actually black not white, since Spanish colonizers in the early 17th century had brought and later abandoned 100 slaves in what is now South Carolina.In the sea islands of Georgia and South Carolina, Gullah is perhaps the best documented and notably the only African American creole whose West African originis remain uncontested.The dramatic increase in slaves in Alabama, Mississipi, and Luisiana from 1820-40 thus began what has been called the “southernization” of Black English.According to some researchers, large concentrations of slaves on a single plantation allowed for more intese linguistic interaction and some limited measure of family life, both of which led to a sustained community (Dillard, J.L. 1972. Black English: its History and Usage in the United States. New York: Random House.). But as mentioned earlier, plantations would not necessarily have been the boundaries of all social life. Under conditions such as these, the creole hypothesis is a distinct possibility, although in amny areas by the late 1800s it also appears that AAVE was undergoing a reverse process of decreolization inwhich features that were noticeably unlike the mainstream varietY (e.g. anterior verb markers such as de and blan) were being lost (Mufwene, S.S. 1997. ‘Gullah Development: Myth and Socio-historical Evidence’ in Berstein, C., Nunnally, T. and Rabino, R. (eds.) Language Variety in the South Revisited: The University of Alabama Press.)Historical linguists mark the final stage in the evolution of AAVE from Emancipation throught the endo fo World War II. During this time a large number of newly liberated slaves began to congretate in isolated rural areas throughout the South (due largely to discriinatory policies established by the majority of white reisents, but in many cases through their own inititatives) to found all-black settlements.195: The increasing monoculture of commercial television that began in the 1950s has had a leveling effect not only on AAVE but on many regional dialects.The dying out or maintenance of minority language vaireties despite (or often in spite of) social or racial persecution is an historical phenomenon well documented by linguistst and ethnographers (cf. Edwards, J., Language 1985. Language, Society and Identity. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.).